When I first encountered ZBiotics Sugar-to-Fiber, I was curious. This probiotic claims to change sugar into fiber in your gut. If it truly works, it challenges our notions about dietary sugar, gut health, and even cancer metabolism.

As usual, I approach these innovations with both interest and skepticism. In cancer discussions, claims about metabolism, sugar, and tumor growth often get exaggerated.

Here’s a closer look at what Sugar-to-Fiber claims, its scientific basis, the evidence supporting or contradicting it, and what it could mean for someone dealing with cancer.

What Is Sugar-to-Fiber and What Does It Claim?

ZBiotics Sugar-to-Fiber is a genetically modified probiotic designed to produce an enzyme called levansucrase. This enzyme aims to convert some dietary sugar, specifically sucrose, into a fiber known as levan in your gut. On their product page, ZBiotics states:

“ZBiotics® Sugar-to-Fiber is engineered to turn sugar into fiber in your gut. It produces an enzyme called levansucrase, which makes fiber using sugar from your diet gently and all day long, supporting gut health and microbiome diversity.”

Their “How it Works” page describes how the engineered probiotic takes sucrose, splits it, and uses the fructose part to create chains of levan fiber.

They also make a crucial point:

“Sugar-to-Fiber is unlikely to break down enough sugar to change caloric intake, blood sugar levels, or weight.”

So, in their own words, this isn’t a “cure for sugar metabolism” but a way to convert a fraction of sugar into fiber, which supports microbiome diversity.

They published a blog introducing the product, and media coverage has referred to it as “the first probiotic that transforms sugar into a special fiber to support gut health.”

That summarises the product claims. Now, let’s look at how well these align with biological reality.

The Science Behind Levan, Levansucrase & Sugar Conversion

To assess Sugar-to-Fiber, we need to consider three aspects: the enzyme (levansucrase), the fiber (levan), and the gut environment.

Levansucrase & Levan: What They Are

Levansucrase is an enzyme found in many bacteria. It facilitates the joining of fructose units to form levan, a fructan polymer, from sucrose.

Levan is a fructan polysaccharide, a fiber primarily composed of fructose molecules linked by β-(2→6) connections.

In microbial and fermentation settings, researchers have engineered systems using levansucrase to produce levan. For instance, a 2024 study discussed strategies that achieved a levan yield of up to 52 g/L from sucrose using bacteria. This indicates that the enzyme method is feasible in optimal lab conditions.

A review article titled “Recent Developments and Applications of Microbial Levan” discusses the engineering of levansucrase systems, yielding challenges, substrate specificity, and polymer characteristics.

So, chemistry and enzyme biology lend support to the idea that sucrose can be converted into levan under suitable conditions.

What Happens in the Gut: Key Barriers

However, the human gut is not an ideal fermenter. Several challenges suggest that actual conversion might be limited:

- Competition with human digestion: In the small intestine, human enzymes (sucrase) quickly break down sucrose into glucose and fructose, which are absorbed rapidly. For the engineered bacteria to act on sucrose, they need to work quickly and in the right place.

- Transit time and dilution: Contents in the gut move, and substances get diluted. The engineered probiotic must have a sufficient population density near the sugar and maintain enzyme production.

- Enzyme kinetics: The rate of conversion is influenced by factors like the Michaelis-Menten constants (Km, Vmax), substrate levels, pH, and cofactors, all impacting how much sucrose can be diverted.

- Microbiome ecology: The engineered strain must compete with native microbes, withstand stressors like antibiotics, pH changes, and bile salts, and avoid being outcompeted.

- Metabolic balance: If fructose is used in the polymer, what happens to the glucose? It might still be absorbed. The overall effect could still release sugar into the bloodstream.

- Safety and gene transfer issues: As with any genetically modified microbe in the gut, there are uncertainties about gene transfer, interactions with resident bacteria, immune responses, and long-term stability.

Therefore, while lab enzyme systems indicate good yields, achieving consistent and significant conversion in humans is complex and filled with variables.

- Sugar-to-Fiber & Cancer Metabolism: Where the Link Might Lie (and Where It Likely Doesn’t)

- Now we reach the key question: Could Sugar-to-Fiber significantly affect cancer metabolism, particularly glycolysis or the Warburg effect, in humans?

First, let’s revisit cancer’s reliance on sugar.

Warburg Effect, Glycolysis, and Cancer

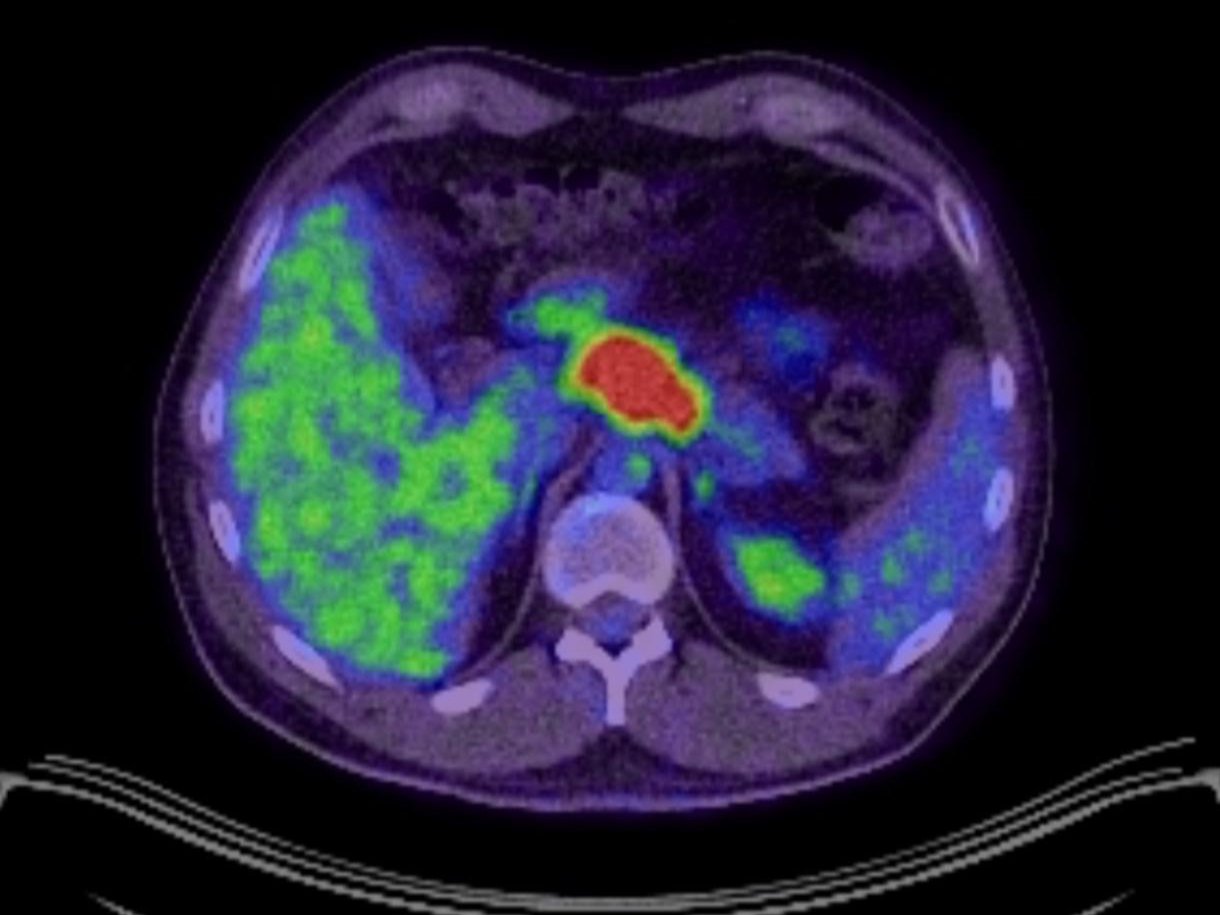

Many cancers exhibit aerobic glycolysis, known as the “Warburg effect.” They convert glucose to lactate even in the presence of oxygen, which supports rapid cell division and production of building blocks.

A recent review, “Modulating Glycolysis to Improve Cancer Therapy,” highlights how targeting enhanced glycolysis could be a promising addition to therapy. It explains that cancer cells change their metabolism to increase glucose uptake, upregulate glycolytic enzymes, and compete intensely in their environment.

Another article, “Glycolysis, the sweet appetite of the tumor microenvironment,” discusses how cancer cells alter nutrient usage, drive lactate production, and shape their surroundings.

The idea is simple: by reducing available glucose, we may stress tumors. However, tumors are adaptable and can turn to other fuel sources like glutamine or lipids when glucose is scarce.

Could Sugar-to-Fiber Help Shift the Balance?

If Sugar-to-Fiber manages to divert a significant amount of sugar into non-absorbable fiber (levan), it could have several potential effects on tumors:

Potential positive outcomes:

- Reduced glucose flow: If less glucose enters the bloodstream, systemic glucose spikes are moderated, which could lower insulin/IGF signaling that fuels tumor growth.

- Lowered glycolytic substrate: Tumor cells, which rely heavily on glucose, could face resource shortages.

- Microbiome and SCFA effects: The fermentation of levan by resident microbes might produce beneficial short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which support gut barrier function, reduce inflammation, and possibly have systemic anti-cancer effects.

- Complementary metabolic stress: Together with other metabolic therapies (like a ketogenic diet or glucose restriction), even a small reduction could create a more stressful environment for cancer cells.

However, numerous caveats suggest this may not be very effective:

- Fraction diverted is likely small: Due to various enzymatic and absorption challenges, even a well-functioning probiotic might only intercept a few grams of sugar each day – far too little to starve a tumor.

- Cancer adaptability and alternative fuels: Tumors can quickly adapt. They can switch to other fuel sources or increase glucose transporters to gather leftover sugar. Studies show cancer cells evolve under nutrient stress.

- Normal tissue competition and systemic needs: Healthy tissues also require glucose; any reductions must be modest enough not to harm healthy cells. Diverting too much could stress normal tissues.

- Interpatient variability: Different cancers, metabolic environments, and patient conditions mean that one person’s tumor may react differently than another’s.

- Lack of human data: Currently, no published trials show that a product like this affects tumor metabolism, survival, progression, or recurrence.

The chances are that this would apply a subtle pressure rather than serve as a major metabolic therapy.

Supporting & Contradicting Evidence (Levan, Antiproliferative Effects, etc.)

It’s important to see if levan has any potential anti-cancer properties or related effects that might offer indirect evidence.

One rat study found that dietary levan improved colon mucosal thickness and had prebiotic benefits.

In vitro, levan polysaccharide has shown antiproliferative effects on cancer cell lines. For instance, one study titled “Antiproliferative effects of levan polysaccharide against colorectal cancer cells mediated through oxidative stress-stimulated…” revealed that levan inhibited the growth of colorectal cancer cells in vitro.

Another earlier study examined levan from microbial sources on MCF-7 breast cancer cells. It found time- and concentration-dependent antiproliferative effects, along with the induction of apoptosis and oxidative stress.

These cell studies are intriguing – they suggest that levan might have bioactive roles beyond being just fiber. Yet, in vitro studies are far less complex than real human conditions.

Additionally, the type of levan tested in those studies likely differs significantly from what a probiotic would produce inside the body.

While levan shows some anti-cancer potential in isolated studies, that doesn’t ensure it will have the same effects produced in the gut by Sugar-to-Fiber.

What I’d Try, Monitor & Be Wary If I Used It

If I decided to experiment with Sugar-to-Fiber as part of a cancer-supportive plan, here’s how I would go about it:

What I’d Do

- Run a short, monitored trial (30-90 days) during a stable period (not when experiencing peak toxicity).

- Establish baseline labs: fasting glucose, insulin, HbA1c, C-reactive protein, and detailed metabolic panel.

- Monitor post-meal glucose levels (using glucose meters) to see if sugar spikes decrease.

- If possible, test stool and microbiome samples for evidence of levan fermentation.

- Track symptoms and tolerance: any gastrointestinal upsets, bloating, or bowel changes.

- Pair it with a low-processed, low-sugar diet so I’m not relying on it to fix an unhealthy diet.

What I’d Monitor Closely / Be Ready to Stop

- Unexpected gastrointestinal issues, bloating, or discomfort.

- Worsening lab markers (like increased inflammation, kidney function, or liver enzymes).

- Signs of microbial translocation in people with weakened immunity (though this is speculative).

- If undergoing treatments like chemotherapy, radiation, or antibiotics, I would consider pausing its use.

- If tracking tumor markers, pay attention for any changes in acceleration or deceleration.

What I’d Be Skeptical Of / Not Expect

- I wouldn’t expect dramatic reductions in tumor size or a metabolic “cure.”

- I wouldn’t rely on this as a primary treatment; it should complement diet, lifestyle, and conventional treatments.

- I would be cautious of overpromising; many products make inflated claims in the cancer metabolic field.

Key Takeaways

ZBiotics Sugar-to-Fiber is a genetically engineered probiotic that aims to convert some dietary sucrose into levan fiber in the gut.

The mechanism (levansucrase converting sugar into levan) is scientifically plausible, but the human gut presents challenges such as competition, absorption, transit, and microbiome variability.

To ZBiotics’ credit, their disclosures mention that the product is not likely to significantly affect caloric intake or blood sugar. They primarily describe it as a tool for increasing microbiome fiber diversity.

Cancer cells often depend on glycolysis (the Warburg effect). In theory, reducing glucose availability could stress tumors, but the adaptability of tumors and their use of alternative fuel sources lessen this possibility.

Some isolated studies indicate that levan could have antiproliferative or active effects in cell lines, but this does not ensure such effects when produced in the body.

If anyone considers using this during their cancer journey, it should be done cautiously and with monitoring, as an adjunct – not as a metabolic cure.

Subscribe to stay connected