18 to 31 December 2024

A week after Cornwall, the power cut, and the cold pool that reminded me of my nervous system, the real storm began. This chapter marked the transition of the plan from paper to reality. It also highlighted the clash between optimistic strategies and the harsh realities of chemotherapy. If the earlier posts focused on gaining autonomy, this one explores what happens when autonomy sits in a vinyl chair, offers an arm, and hopes the science you’ve relied on holds up.

I’ll be candid. It wasn’t easy. It was necessary. There were moments that reminded me why I was fighting.

18 December – Infusion Day

They don’t tell you that chemo days resemble flights. You arrive early, feeling listless, with a bag of items that make you feel more human under harsh lighting. I arrived at Bracknell Healthspace at 8:30 AM, relieved that the car park here didn’t require a PhD and a prayer like Royal Berks did. I signed in, sat down, and chatted lightly whilst waiting for something significant to happen.

The day passed in a series of numbers. Blood test outcomes. Consent reconfirmed. Observations. A seat assigned among the quiet arrangement of recliners and drips. Plastic rustled. The cannula slid in. The nurse was kind in a way that comes after someone has inserted a thousand cannulas and knows it can sometimes be the worst part.

Oxaliplatin, the cold one, entered my bloodstream first. Then came the rest of the (CAP)OX routine. Pembrolizumab, the immunotherapy, arrived with less fanfare than you might expect from a drug with so much attention. I watched the bags move like changing weather and jotted down a few notes I wouldn’t revisit because the room was filled with low murmurs of quiet courage and lots of sombre looking faces.

I walked out at 6:30 PM, the winter darkness well underway and pressing against the windows. Ten hours, give or take. A day counted in drips, not by clocks.

What CAPOX Actually Is – In Simple Terms

CAPOX consists of two drugs that work better together than separately.

Oxaliplatin is a chemotherapy drug based on platinum. Think of it as a shape that slips into cancer cell DNA and disrupts it, causing the cell to miscopy itself. Cells that divide quickly tend to trip more often. Side effects come with that aggression – nerve irritation that makes cold feel electric, jaw tightness when sipping water, tingling or numbness in hands and feet – Neuropathy.

Capecitabine is an oral drug taken at home. It’s a pro-drug for 5-FU, meaning your body converts it into the active chemo molecule in tissues where it’s needed most. The goal is to maintain pressure on the tumor between infusions, creating a steady background noise that cancer cells hear while your normal cells can partially tune it out.

Together, they aim to disrupt the frantic copying that allows cancer to thrive.

Pembrolizumab – The Immune Boost

Pembrolizumab is an immune checkpoint inhibitor, an antibody that blocks a protein called PD-1 on T-cells. When PD-1 is engaged, T-cells behave as if they’ve been told to stand down. Some tumors exploit this, whispering “nothing to see here” to the immune system. Pembro stops that whisper from sticking. It doesn’t kill cancer directly. Instead, it attempts to activate your immune system so it can recognise what it has been trained to ignore. My PD-L1 result was borderline – just under the usual threshold – but my oncologist still pushed to get me on it. Credit where it’s due.

In short: CAPOX is the hammer. Pembro invites the bouncer back into the room.

Whilst all this sounds great in theory, inside a body, it feels less graceful.

Swallowing the Difficult

By the end of day one, I learned that the side effects pamphlet is just a pamphlet, not a prophecy. My oesophagus felt like a spiteful passage. Anything I attempted to swallow faced resistance, then pain. One team member advised me to mix the capecitabine with juice to help it go down due to my swallowing issues. It worked. It was also a daily reminder that my throat had become a battleground.

A necessary note here: I did this under medical advice for my situation. Please don’t crush, split, or dissolve any medication unless your clinician advises you to.

Chemo has a distinct taste and rhythm. The taste is metallic, like a coin under your tongue. The rhythm is a lag – feeling normal, then not, wondering if it’s all in your head, until your nerves start signaling through your fingertips when you touch something cold and your jaw tightens when you drink water as if you were chewing ice. Oxaliplatin is known for this effect; they even serve drinks slightly warm on purpose.

The antiemetics I had at that time didn’t suit me, so the nausea persisted. Food lost its familiar taste. Smells became unwelcome. Christmas ads showing anything sizzling felt like attacks.

20 December – Amanda King and the Language I Needed

Two days after the infusion, I met Amanda King for an initial consultation. If this seems too soon, know that urgency can alter calendars.

Meeting Amanda felt like finding a manual for a machine I had been assembling blindly with crazy youtube comments knocking me off path all over the place. She didn’t romanticise anything or dismiss my concerns. She spoke science fluently and compassionately. She considered my vegetarian keto, the metabolic theories, and the challenges of a body that hated swallowing. She provided a framework that wouldn’t collapse under pressure. I’ve met many exceptionally bright people along this journey. Amanda was one of the first to communicate with me at my level – fast, precise, no fluff. I left that call with three new questions for every answer, which indicates you’re in the right place.

I wish I could elaborate more here, but the A-Team post shares her story in more detail. However, this date is significant in the timeline. Two days after chemo, we added a mind I trusted to the team. That helped, even if my body hadn’t kept pace yet.

21 to 23 December – Pain and Urgency

By the twenty-first, the pain shifted back from background noise to sharp, stabbing sensations again. This wasn’t the dull ache of a familiar foe. It was rhythmic, with my oesophagus and gut taking turns, like someone had replaced my insides with a bag of cutlery and was shaking it. Likely chemo-induced, in an already irritated environment. I called the 24-hour oncology helpline – as you’re instructed to do. They were efficient and kind. An ambulance was dispatched with lights and sirens. There’s a strange shame in rushing to the hospital when you feel slow.

This time, I was admitted directly to the majors, a few hours wait in A&E for a bed. The destination was a palliative ward. If that word unsettles you, mine sank. In reality, palliative doesn’t mean you’re being written off; it means focus on symptom control and quality of life. Still, it’s hard not to hear it as a judgment at thirty-five, especially with a Christmas tree in your peripheral vision.

They raised my oxycodone, kept the pregabalin, and connected me directly with the palliative care team for pain management instead of routing me through oncology every time. This practical change – having the right specialists handle the right issues – matters more than many realise. When the right team treats your pain, relief becomes a goal rather than a happy accident.

Nights in a ward have a distinct sound. Monitors beep like distant birds. Curtains breathe. Nurses move with the quiet authority that comes from years of hard work. On the second night, the patient in the bed next to me passed away loudly and abruptly. It was quiet, then loud, then quiet again. Sleep became impossible. I stared at the ceiling, counting fluorescent lights and thinking unhelpful thoughts about what songs I would want played at my own funeral service. Then I told my mind to settle down and be quiet because I had work to do tomorrow – staying alive.

On the afternoon of the twenty-fourth, I was discharged. I left with a bag full of medications and instructions, along with the assurance of a phone that would be answered if I needed it. Yes, I was exhausted. Absolutely, I was fragile. But home was still within reach.

Christmas Day – Superhero Medicine

I made it home in time for xmas, in our little world. No large family gathering. Just Ana, the boys, and me. Less noise, more reality.

The house embraced Christmas with careful courage. I was upright, then flat, then upright again. Food was a negotiation. Smells were still the enemy. However, home smelled better than the wards. Even tired air felt like a warm embrace when it’s your own.

There was an emotional void where Mum should have been. I felt it in the pauses. I missed Duke in the corners – the empty space where his bed used to be, the way the day once moved to a dog-shaped rhythm, the big slobbery cuddles and nose pokes of care. That kind of grief doesn’t announce itself. It quietly resides on the couch and waits for you to notice.

Then Axel handed me a present with the serious demeanor only a small boy can muster. His school had created a Santa gift table where children could choose a gift for their parents. Grandpa Sam (my dad) had taken him while we were in Cornwall – the school had very kindly set up and let him do it early, knowing he’d have to be away from school when I went into chemo (due to the immune issues it creates). Axel picked a Superman aftershave set. Somehow, at only 3 years old he’d managed to keep it quiet for over a month. On Christmas Day, he explained why – because it was superhero medicine to help Daddy fight Dave. Dave, in case you’re unfamiliar, is the name Axel gave my cancer. Naturally. Naming a monster makes it less frightening.

I opened it and tried not to cry. Then I stopped pretending. If you need a reminder of why someone would endure a process that feels like poison and a courtroom at once, I can suggest a small child sharing faith with an aftershave set. It does the trick.

The Slow Nature of Side Effects

Chemo isn’t a one-time event. It resembles a weather system. The cold neuropathy from oxaliplatin was immediate and hard to ignore. Touch anything cold and your fingers spark. Breathe cold air, and your throat tightens as if you swallowed a glove inflated with nitrogen. Water takes on a strange texture. Metal utensils become foes. You learn to warm the glass, wrap the mug, and breathe through a scarf in your own kitchen.

Nausea didn’t just hit; it built over time. The antiemetics (anti-sickness meds) they’d prescribed weren’t effective for me, so every smell had its own harshness. The fridge felt like a crime scene. Even thinking about food made my stomach rehearse its escape plan. I spent nearly a week in bed, engulfed in the post-chemo haze, counting small victories: a couple of hours without waves, a few hundred steps indoors without lying on the floor, and a sip of lukewarm water that didn’t punish me for trying.

There’s always a quiet triumph hidden within if you look for it. Just standing up counts.

What the drugs were doing whilst I hated them

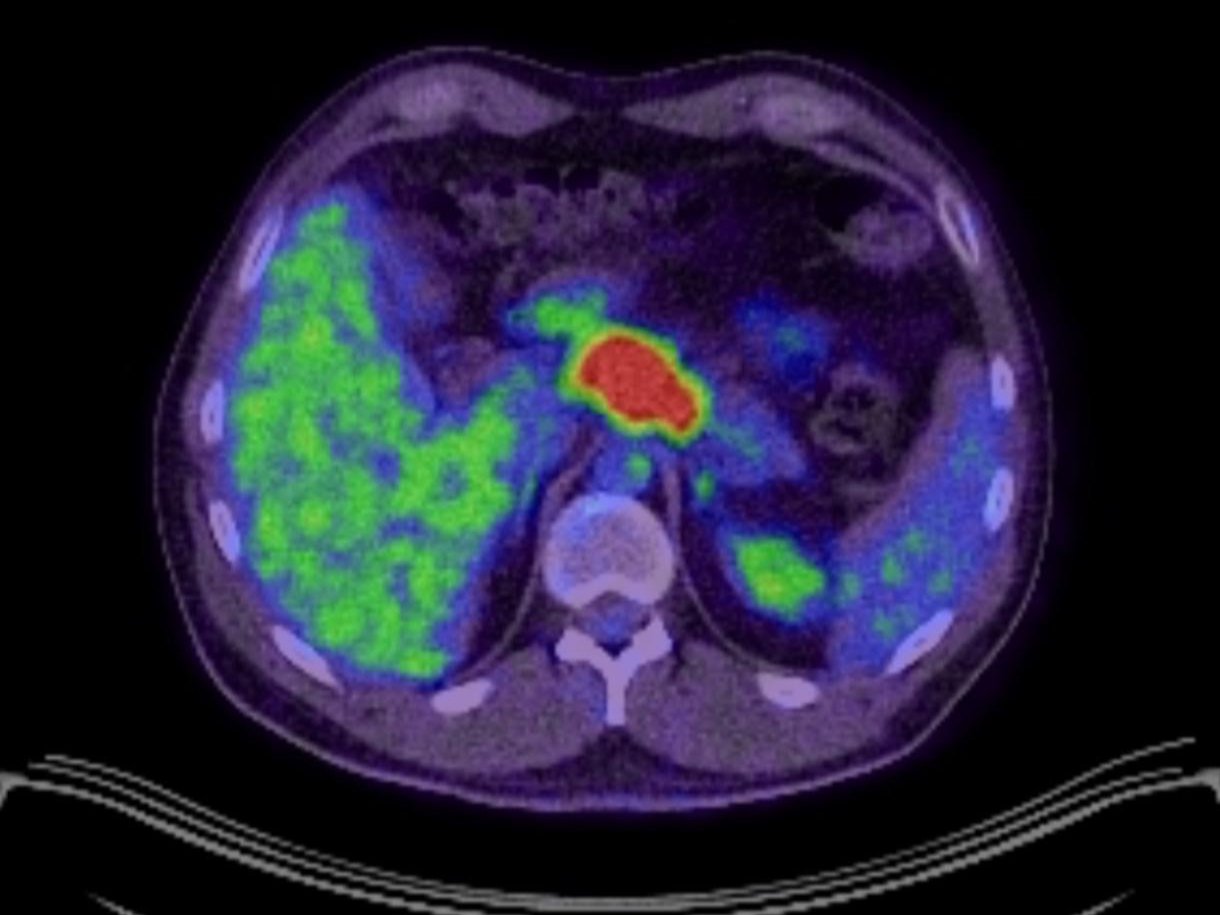

When your body complains about side effects, it's easy to see the drugs as the enemy. I'm not a martyr. I complained. But I'm also a realist. Whilst I was curled up in blankets and negotiating with my stomach, CAPOX was delivering a biochemical blow to cells that had escaped justice. Pembrolizumab was moving through my immune system with wire cutters, trying to release T-cells trapped in a box.

This duality matters. You can appreciate the intent while disliking the method. You can acknowledge that a tool is harsh yet necessary. Your reaction doesn’t reflect the outcome. The body is not a democracy. The votes are counted in cycles, not social media updates.

The human systems that worked

People tend to either praise the NHS or criticise it. I don't feel strongly about either view. The truth is more nuanced. The nurses at Bracknell were exceptional. The oncology triage line functioned as it should: I called, they listened, they made a plan, and an ambulance arrived so quickly I wondered if it had been waiting nearby. The palliative team transformed pain from a personality trait back into a symptom with a clear pathway. All of this matters.

It's also true that my antiemetics weren't right at first, and we needed to adjust later. That matters too. These aren’t contradictions. They show how large systems work: brilliantly in some areas, imperfectly in others. Gratitude and critique can coexist without undermining each other.

The light that slipped in

There were small mercies. A shower felt like being allowed back into my own skin – albeit I had to buy a little stool, as I couldn’t stay upright long enough to finish my shower. A morning when the pain stayed in the background instead of taking control. A nap that left me feeling half-human instead of like a ghost. The smell of my boys’ hair. Ana sitting on the edge of the bed, reading something she’d read, and rolling her eyes for me. The house buzzing with the quiet heroism of laundry and Lego.

Sometimes survival looks like a man holding a mug with both hands because the nerves in one hand don't trust the other, deciding that this counts as a win. It does. It did.

The year closed, not with a bow, but a line in the sand

By the thirty-first, I didn't feel triumphant. I wasn't even steady. But I was home. The first round had hit hard. It knocked me sideways, then down, then allowed me to lean against a wall in my own house whilst the room stopped spinning.

I reflected on the few months we’d had. Duke had moved on to his new life, because love sometimes means closing a door behind you. Mum was gone, the crack in the windshield, left by my dads umbrella at mum’s funeral, felt like a metaphor for the last few months. The consent room where fear came close to winning. The nurse who spoke the sentence that gave me hope. The V8 key in my pocket, both absurd and essential. The nights on the gurney and the ward that echoed endings. And now, the vinyl chair that marked a different kind of beginning.

I also thought about Axel’s Superman medicine and how a small boy confronts a big problem. I imagined him looking at a shelf of choices and picking belief. You can build a year on that.

If you're expecting me to say this first round felt like a victory, I’d be lying. It felt like a struggle where you get sick between rounds and deceive your corner about how well you can see out of your right eye. But the bell rang. I stood up. The year ended with me still standing. And if you're wondering if that matters, let me be clear: it really does!

Chemo didn't define me. It didn't even define the month. It was a chapter. Hard, necessary, brutal at times, and clarifying in others. Round one over. No knockout. We go again.

Next time, I’ll write about how the system around me – the team, the protocols, the daily routines -started turning chaos into clarity. How the numbers began to matter. How sleep returned in small bits, then more. And how, even before scans confirmed it, the shape of hope began to look less like a wish and more like a plan.

For now: the year closed. I was still here. And in this journey, still here is a powerful statement.

Subscribe to stay connected