One of the hardest parts of a stage IV cancer diagnosis isn’t just what it does to your body. It’s how it changes the people around you.

People don’t talk about this much. They discuss treatment options, prognostic charts, and tumour markers. They don’t talk about the way your world quietly rearranges itself around you. How some people step towards you with both arms outstretched, and others back away so gently you almost miss the moment they’re gone.

Cancer is a strange kind of centrifuge. It spins your life fast enough that the non-essentials fly off… and what’s left is very, very real.

This is a chapter about the ones who stayed-the people who moved closer as everything else fell apart. I’ve already written about the A-Team-the integrative oncologists, metabolic experts, and naturopaths. Now it’s about the inner circle: the humans who made using science possible.

Without them, there is no protocol, no discipline, no “Killing Dave” story. There is just a very sick man and a family trying to survive.

When the Room Empties, You Notice Who’s Still Sitting There

Before we focus on the good ones, it’s important to note the shift that happens.

Some people quietly disappear when you get a terminal diagnosis. Not because they’re evil or unkind, but because death is a mirror and they don’t like what it shows them. They don’t know what to say. They’re terrified of saying the wrong thing, so they say nothing. Messages tail off. Plans evaporate. You become “too much”.

I don’t hold a grudge about that. Most of us are raised in a culture that avoids real conversations about illness and mortality; we aren’t given a script for this.

But the contrast matters. When the room empties, the people who are still sitting there – still bringing tea, still asking real questions, still turning up when it’s awkward and exhausting – become the pillars of your survival.

My pillars had four names: Ana. Jo. Dad. Mark.

Ana – The One Who Refused to Break Before I Was Safe

Every story about my survival has to begin with Ana, because without her, there is no story – just a collapse.

By the time my cancer showed up, she’d already fought her own. Shoulder, chest and neck pain. A suspected heart issue. An X-ray showed a small nodule deep in her lung. No easy biopsy option. Meetings with specialists, then a surgeon. Major lung surgery on 3 October. Home by the 5th. No lifting. No exertion. No carrying children. No normal life for a while.

Just ten days after Ana’s return home, I was lying on a hospital bed, hearing the news that a tumour had been found in my oesophagus.

Most couples don’t encounter cancer together so closely in time. We had a double bill within weeks.

From that point on, Ana became the operational core of our lives. Whilst I was falling apart physically, mentally and chemically, she was holding everything else up – the house, the boys, the appointments, the admin, the logistics, the emotional tone of the whole operation.

And here’s the thing that still floors me: she didn’t let herself break.

She didn’t sob on the kitchen floor after appointments. She didn’t scream into pillows at 3am. She didn’t unload her fear onto me, even when her own chest was held together with staples and scar tissue.

She went into a kind of controlled emotional lockdown. Not because she didn’t feel it, but because she decided – consciously or not – that someone in the house had to keep functioning.

There were unspoken rules between us:

- I would keep turning up to treatments, protocols and appointments, no matter how awful I felt, because she needed to see me fighting.

- She would keep the boys’ lives as stable as humanly possible, so their childhood memories weren’t just hospitals and hushed conversations.

- I wouldn’t tell her every time I thought, “This might be it.”

- She wouldn’t cry in front of me, believing it might be what finally cracked me.

Are those rules sustainable long-term? Of course not. But in the early months, when everything felt held together by surgical tape and caffeine, they gave us structure.

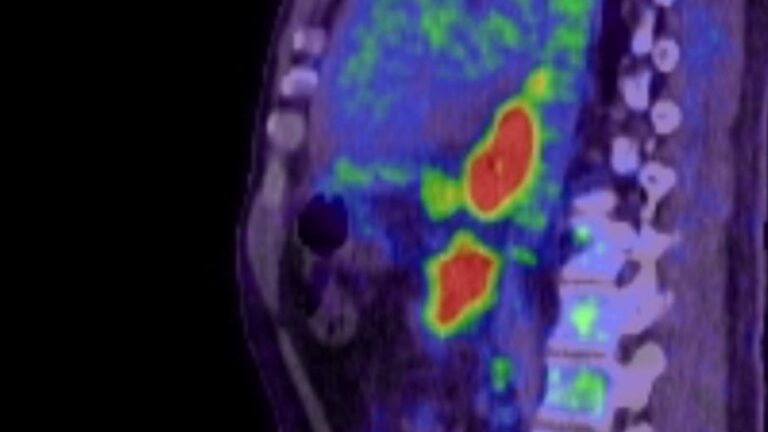

It wasn’t until much later – after the scan that showed the metastases were gone – that she finally let herself cry. Properly. The sort of crying that comes from three hundred days of holding your breath.

She didn’t cry because the scan was good. She cried because she’d finally been given permission to.

That is the scale of what she carried.

Jo – The Nurse Who Became Family

If I tried to draw a map of all the things that needed to line up for me to still be here, there would be an arrow pointing at Jo with the label: “This was not an accident.”

I’d known her from my time living on Guernsey about a decade earlier. Not “best friend” close, but solidly in the category of “good person, good nurse, someone you instinctively trust”.

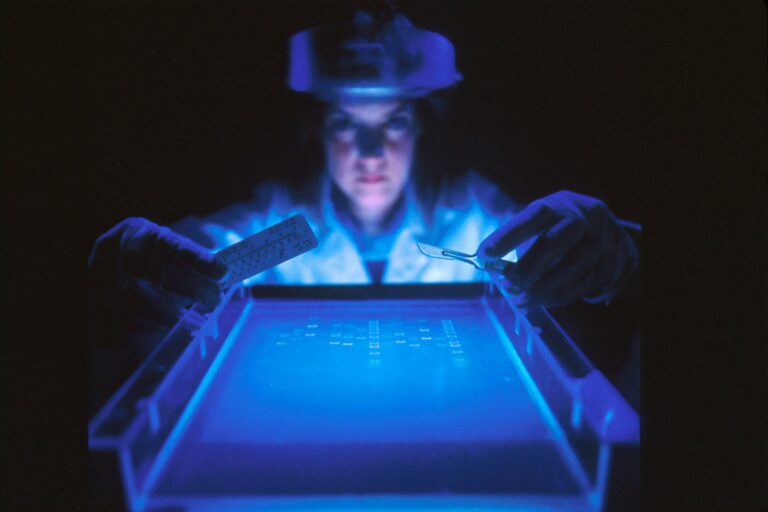

When the time came to start high-dose vitamin C and more complex IV work at home, we hit a wall. The hospital system wasn’t built for the kind of integrative approach I was taking. Appointments were limited. Oncology had its hands full. And I was running out of bandwidth to chase solutions.

So I did what desperate people do: I reached out.

“Any chance you’re anywhere near Reading?” I asked, half-expecting a polite apology and a “sorry, not local”.

She lived ten minutes away.

You couldn’t script that.

From then on, she was in our house two to three times a week, every week. Placing cannulas. Overseeing infusions. Keeping an eye on my vitals. Catching things early. Explaining things clearly. Translating the madness of medicine into human language.

But she didn’t just bring clinical skill. She brought atmosphere.

There’s a way some nurses walk into a room, and you immediately feel your shoulders drop a few centimetres. That was Jo. The boys took to her immediately – she became “Auntie Jojo”, the friendly grown-up who turned up with calm energy and made the scary medical stuff look normal.

In a life that had become sharp around the edges, she was soft but steady. Not in a sentimental way – in a grounded, practical, “we’ve got this” way.

Metabolic cancer protocols are complicated. They demand consistency. They demand monitoring. They require that someone notices when things aren’t right. Without Jo, half of what we tried to implement at home would have been impossible.

You can build the best plan in the world on paper. Without a Jo, it stays on paper.

My Dad – The Stoic in the Background

If Ana is the fortress and Jo is the medic, then my dad is the mountain in the background.

He grew up in places that harden you by default – He was born in Uganda and sent off to a family friends borstal at 5/6 – the child of agriculturalists working for the British government. The kind of upbringing where resilience isn’t a personality trait, it’s a survival requirement. He started smoking at five, when they were based out in the Kalahari, because that’s what people did back then, and nobody stopped him.

Emotionally, he’s from a different generation. He doesn’t talk in feelings. He doesn’t do long heart-to-heart monologues. But when things go wrong, he turns up.

It’s his reflex.

During those months, he came over again and again. To stay with the boys whilst Ana came with me to appointments. To be there when big conversations were happening. To help with practical stuff around the house. To quietly patch over the gaps so things didn’t collapse.

He never made a show of it-just appeared, slotted into the chaos, and did what needed doing: cooking, childcare, driving, cleaning, fixing.

He also helped financially, and whilst I don’t want to dwell on that, it mattered and still does. Cancer isn’t just a physiological event; it’s an economic one. When work stops but bills don’t, having someone step in so you don’t lose the house is the difference between “hard” and “catastrophic”.

What I appreciate most, though, is that he didn’t ask me to manage his emotions on top of my own. I could see he was scared. You don’t watch your eldest son go through stage IV cancer, and your ex-wife die, and stay untouched. But he kept that weight off my shoulders as much as he could.

Most of the time, he simply sat in the house with us. Not filling the space with chatter. Not forcing optimism. Just being there. You learn to value that kind of presence in a way you never do when life is easy.

Uncle Mark – The Friend Who Acted Like Family

Then there’s Mark – known in our house as “Uncle Mark” and to Axel as his godfather.

Some friendships are light-touch: messages, memes, the occasional beer. Others quietly deepen over time until, one day, you realise this person has drifted from “friend” into “family”.

Mark is firmly in the second category.

I met Mark when we were both living out in Shanghai doing work placements some 20 years ago – we shared a room together in a cramped little flat in shanghai – we became instant friends and were an inseparable pair throughout our time in China.

By the time everything kicked off with my diagnosis, he’d already been a consistent presence in our lives since I moved to London in 2017, but his impact during that period was… different.

When Ana and I went to The Scarlet in early December – our pre-chemo lifeline trip – it was meant to be a chance to breathe. To talk about death and life and wills and wishes and, occasionally, something as mundane as what we might cook when all this was over. It was emotional, fragile and desperately needed.

What we didn’t know until later was that he’d quietly called the hotel and paid for the whole stay.

No fanfare. No “look what I’ve done”. Just a quiet act of generosity at a time when everything felt heavy and precarious.

He’s been there in countless other ways, too – small check-ins, solid advice, presence at key moments – but that gesture is emblematic of something bigger: he noticed we were drowning and threw us a rope, without needing credit for it.

You can’t ask that of people. They either do it or they don’t.

The Ones Who Drifted – And Why That Makes the Inner Circle Matter More

It would be dishonest to pretend everyone rallied.

Some acquaintances disappeared. Some friends went quiet. Some people sent one deeply awkward message, then never followed up. A few edged around me at social events, as if I were carrying something contagious.

I don’t say that bitterly. I understand why it happens, and I’ve long since made peace with it all. Serious illness triggers people’s own unresolved fear, grief, and trauma. They might be reminded of relatives they lost. They might not have the emotional language for this. They might be in their own private crisis.

But here’s the psychological truth of it: when you are at your lowest, your brain is already scanning for threats and abandonment. Every silence feels louder. Every missing reply stings more than it should.

And that’s why the inner circle matters so much.

When your world is shrinking, and some faces fade into the distance, the ones who keep showing up become disproportionately powerful. They are the difference between feeling fundamentally alone and feeling held.

Ana, Jo, Dad and Mark didn’t flinch. They walked towards the mess instead of away from it.

They weren’t perfect. Nobody is. There were misunderstandings, frayed tempers, exhausted conversations, moments where everyone was doing their best on an empty tank. But they stayed. In a situation where leaving would have been easy, they consistently chose not to.

Survival Is Never a Solo Achievement

It’s very tempting – especially online – to frame cancer survival as a lone-wolf story.

The warrior.

The fighter.

The outlier who refused to die.

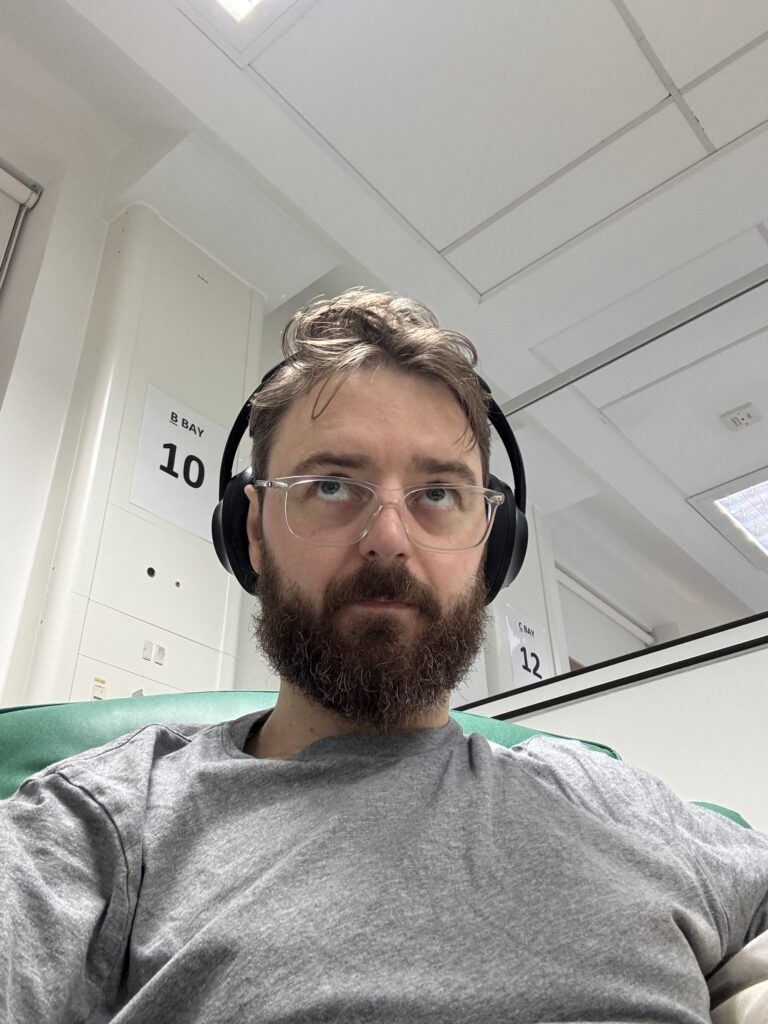

There is a bit of that in my story, obviously. I did my homework. I built a protocol. I took obscene numbers of pills. I sat in pressure chambers and ice baths and saunas and infusion chairs and chemo wards and did my absolute best to turn my body into a hostile environment for Dave (my tumour).

But if you strip away the people, none of it holds.

- Without Ana, the house collapses, the boys lose stability, and I lose my anchor.

- Without Jo, the home-based medical side falters, and half my adjunct therapies never get off the ground.

- Without my dad, the practical and financial floor gives way, and everything becomes ten times harder.

- Without Mark, we lose some of the emotional oxygen that kept us going.

Survival – real survival – is a network effect.

The scans, the drugs, the protocols, the discipline; they matter enormously. But they sit on top of an invisible scaffolding of human beings, making sure you’re not doing all of this in a vacuum.

If you’re reading this in the middle of your own cancer journey, or walking alongside someone in theirs, I’d offer this:

- If you’re the patient, you are allowed to ask for help. It doesn’t make you weak; it makes you human.

- If you’re supporting someone, the small, consistent acts matter more than the big, dramatic gestures. Being there counts. Staying counts.

My inner circle didn’t cure my cancer. But they made it possible for me to stick around long enough for the science and my stubbornness to do their work.

And if there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s this:

The protocols kept me alive on paper.

The people kept me alive in reality.

Subscribe to stay connected