Find Part 1 Here

And Part 3 Here

Introduction: The Shape-Shifter Problem

If the Warburg effect covered everything, cancer would be straightforward. We could deprive tumours of glucose, watch them shrink, and call it done.

But cancer isn’t just a simple parasite. It’s a shape-shifter.

Some tumours don’t even want sugar. Some thrive on oxygen. Others prefer amino acids, fatty acids, or even lactate as their main source of energy.

This complexity complicates the Warburg story and shows why a “one-size-fits-all” method for cancer metabolism is bound to fail.

When Cancer Breaks the Warburg Rules

1. Prostate Cancer: The Amino Acid Outlier

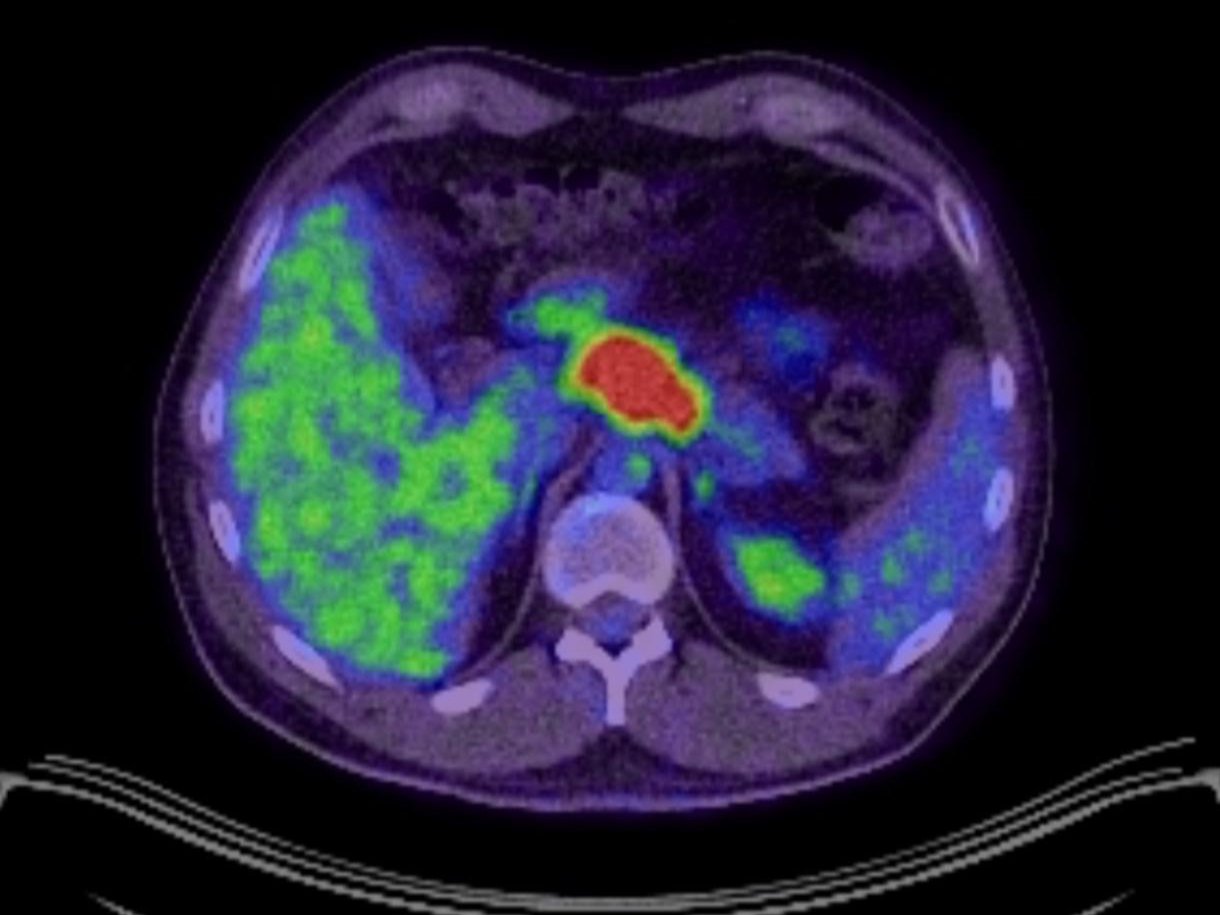

If you depend on PET-CT scans to find prostate cancer, you might often be let down. Many prostate tumours don’t light up at all. Why?

Because they don’t depend on glucose. Instead, prostate cancers often rely on:

- Lipids: fatty acids broken down and used for energy.

- Amino acids: glutamine, alanine, and others, channelled into the TCA cycle.

This is why imaging for prostate cancer uses different tracers, such as PSMA PET, choline, or acetate, instead of glucose.

For patients, this means two things:

- A ketogenic diet might not impact prostate cancer as strongly as it does other tumors.

- Therapies that target lipid or amino acid metabolism could be more significant.

2. Glutamine Addiction

If glucose is the primary villain in the cancer fuel story, glutamine is its equally dangerous partner.

Many tumours – pancreatic, glioblastoma, certain breast cancers, and my own tumour did too – have a “glutamine addiction.” They use glutamine for:

- A carbon source for the TCA cycle (mitochondrial respiration).

- A nitrogen source for nucleotide and amino acid creation.

- A buffer for oxidative stress (by producing glutathione).

Deprive them of glutamine, and they struggle. Unfortunately, glutamine is the most abundant amino acid in the body, making it difficult to target without also affecting healthy cells.

Clinical trials are investigating glutaminase inhibitors as cancer drugs. While it’s still early, this reflects how vital glutamine metabolism is in many tumours.

3. The Reverse Warburg Effect

In some cancers, the tumour cells themselves don’t perform glycolysis. Instead, they get help from their neighbours.

Here’s how it works:

- Stromal cells (the fibroblasts and support cells around the tumor) are recruited to conduct glycolysis and produce lactate.

- The tumour cells then take in this lactate and burn it in their mitochondria through oxidative phosphorylation.

This process is called the Reverse Warburg Effect.

It changes the dynamic: the tumour efficiently uses oxygen, while the surrounding support cells act as a glucose-processing factory.

For patients, this means that even if your tumour isn’t glycolytic, the surrounding environment might still be doing the Warburg metabolic work on its behalf.

4. OXPHOS-High Tumors

Some cancers completely defy Warburg and focus on oxidative phosphorylation.

Examples include:

- Some types of leukaemia’s.

- Melanoma.

- Certain resistant forms within glycolytic tumours.

These tumours depend on mitochondria for energy and growth, often making them more resistant to glycolysis-targeted treatments.

In some instances, they even switch between glycolysis and OXPHOS based on what’s available – a metabolic flexibility that makes them tougher to target.

5. Lactate as a Superfuel

For years, lactate was seen as waste – the substance that causes sore muscles after exercise.

But tumours view lactate differently. Many cancers have transporters (MCT1 and MCT4) that allow them to import lactate and use it as fuel.

This creates a “lactate shuttle”:

- Some cells produce lactate through glycolysis.

- Others take it in, convert it back to pyruvate, and channel it through the TCA cycle.

Lactate isn’t waste here. It’s a high-quality fuel that cancer recycles with ruthless efficiency.

Why This Matters

If cancer metabolism were solely about sugar, the strategy would be simple: cut carbs, add keto, and finish.

But the situation is more complex:

- Some tumours rely on sugar, some on glutamine, some on fat, and some on lactate – and some on all of them.

- Some switch fuels based on availability, showing a metabolic agility that makes them nearly impossible to starve.

- This is why broad claims like “keto cures cancer” don’t hold up. It works for some, helps in many cases (mine included), but it isn’t universal.

The Danger of Dogma

I’ve seen well-meaning patients in forums claim that “all cancer is sugar-driven” – and it’s just not true.

For someone with a glucose-dependent oesophageal tumour like mine, keto and fasting make biochemical sense. But for someone with prostate cancer using fatty acids or a glioblastoma addicted to glutamine, the effect might be weaker or different.

This is why testing is essential:

- Imaging (FDG-PET, PSMA PET, choline, acetate).

- Metabolomics, genomics, next-generation sequencing.

- Clinical response over time.

Cancer isn’t one disease. It’s hundreds of different metabolic types using the same label.

My Perspective

When I began metabolic therapy, it was because my PET scan showed the Warburg effect in full swing. My tumour was undeniably sugar-driven.

But I’ve met people whose scans barely reacted. For them, sugar wasn’t the problem – their tumours had different cravings.

This experience humbled me. It reminded me not to oversell, and not to project my biology onto others. As you’ll regularly see me say on my Linkedin profile: My metabolic strategy works for me. Someone else’s might require a different approach.

Why Exceptions Are Still Useful

The exceptions do not undermine Warburg’s importance – they sharpen it.

- They explain why some scans fall short.

- They show why some diets work for some patients but not others.

- They point to new targets (glutamine, fatty acids, lactate transporters).

- They demonstrate that cancer isn’t fixed – it changes and adapts.

In practice, this means the Warburg effect remains a key part of understanding cancer – but it’s only the starting point of the metabolic story.

Conclusion

The Warburg effect explains why most cancers crave sugar. But the exceptions remind us that cancer is not a single narrative.

Some tumours burn fat. Some burn amino acids. Some burn lactate. Some burn it all.

This doesn’t make Warburg irrelevant – it emphasises its importance, since it’s the foundation for customising therapy rather than the final answer.

For patients, it means avoiding rigid beliefs and seeking precision. For clinicians, it means moving past “one scan, one pathway” and treating cancer as the metabolic shape-shifter it is – and, hopefully, towards personalised cancer care too.

For me, it’s a reminder to stay humble. My tumour may thrive on sugar, but that doesn’t mean every tumour does. This humility might be the key difference between hope and harm.

References

- Boroughs LK, DeBerardinis RJ. Metabolic pathways promoting cancer cell survival and growth. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(4):351–359.

- Pavlides S et al. The reverse Warburg effect: aerobic glycolysis in cancer-associated fibroblasts and the tumour stroma. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(23):3984–4001.

- Yuneva M. Finding an “Achilles’ heel” of cancer: the role of amino acid metabolism. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36(Pt 6):1462–1465.

- Faubert B, Li KY, Cai L, et al. Lactate metabolism in human lung tumors. Cell. 2017;171(2):358–371.

- Corbet C, Feron O. Tumour acidosis: from the passenger to the driver’s seat. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(10):577–593.

- Beloueche-Babari M, et al. Acetate metabolism in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75(15 Suppl):218.

Subscribe to stay connected