On first glance, the old photographs seem wholesome. Families smile as a shop assistant places a child’s feet into a wooden box and invites everyone to look through a viewfinder. The machine was a shoe-fitting fluoroscope, an in-store X-ray. From the 1930s to the 1950s, these devices were promoted as modern magic. They offered safer shoes and better posture. They claimed to use science for our benefit. Yet, the dose was invisible. The risk was invisible. The harm took time to appear and was often disputed. By the time regulators stepped in, reports of radiation dermatitis, burns, and even amputations had already emerged, alongside warnings about dose variability and scatter radiation affecting both staff and children.

I live with cancer. Early on, my eldest son gave the tumour the name “Dave.” It made discussing it less frightening. When I saw the glow-in-the-bones photo years later, I felt a shock of recognition – not because radiology today is unsafe, but because the psychology feels familiar. The system can blur the line between novelty and wisdom. Both clinicians and patients want solutions. Sometimes, in traditional medicine and wellness practices alike, enthusiasm overshadows the evidence.

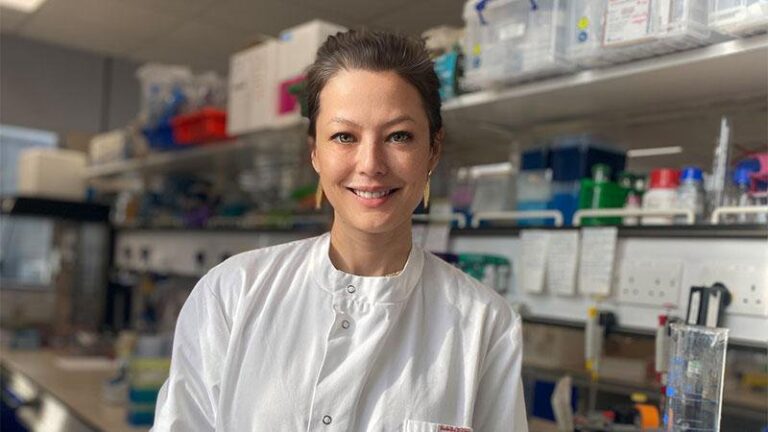

This piece examines that blind spot, both past and present, and how I’m trying to navigate it as a patient. I support science and do not oppose medicine. I underwent chemotherapy, and immunotherapy. I use evidence-based support methods. The key question isn’t old versus new or hospital versus holistic. It’s straightforward: does this help this patient at this moment while understanding and minimising risks?

The shoe shop lesson, when wonder outpaced wisdom

Shoe-fitting fluoroscopes were used in shops across the US, UK, and Europe from the 1920s to the 1960s. They produced live X-ray images showing how toes fit inside new shoes. Studies from that time noted highly variable doses, stray radiation, and clerks’ exposure. Reports of radiation injuries began to surface, and warnings came as early as 1950. By 1957, bans started appearing, and by the 1960s, these machines were mostly removed.

This same era introduced Radithor, which was “triple distilled radioactivity in colloidal suspension,” marketed as a tonic. It ultimately killed socialite Eben Byers after causing jaw necrosis and severe radiation damage. The label promised energy and health, but it delivered harmful alpha particles that lodged in bone.

These examples are not cheap shots at history; they illustrate how progress unfolds – a powerful idea adopted widely, regulated slowly, and corrected later. They remind us that invisible harms often lag behind visible hope.

What changed – modern radiology is not the 1950s

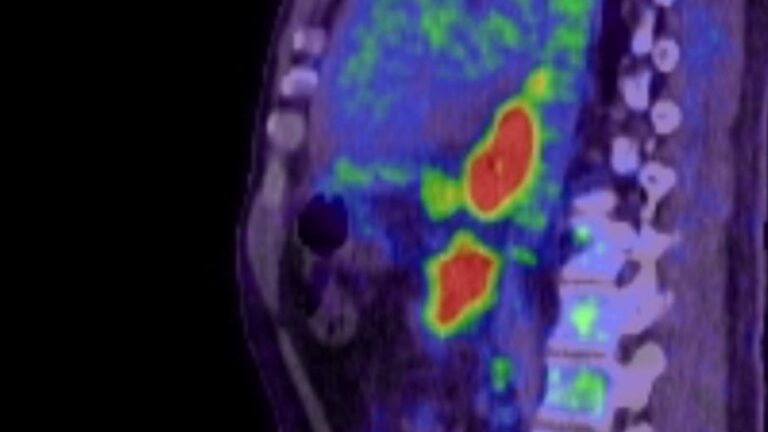

Modern imaging is truly miraculous when used correctly. It diagnoses, stages, and guides treatment with precision that our grandparents could never have imagined. Most importantly, radiology today follows strict ethics and regulations. The ALARA principle, which stands for “as low as reasonably achievable,” requires minimising doses while still providing diagnostic value through time, distance, and shielding. International organisations like ICRP continually update optimisation guidelines, and national agencies teach and enforce best practices.

However, non-zero risk does not equal zero risk. Recent studies suggest that cumulative CT use might lead to a noticeable number of future cancers at a population level, particularly among children and adolescents, who are more sensitive to radiation. Although most absolute risks are small, the clinical benefits often outweigh them. This is not an argument against CT; rather, it emphasises the need for justification, dose standardisation, and avoiding unnecessary scans.

When I meet with my oncologist to discuss imaging, this is the framework I want: focusing on benefits over risks, rather than habits over hopes. The radiology team that staged my disease took this very approach. This is how modern medicine is supposed to function.

Modern miracle machines and modern blind spots

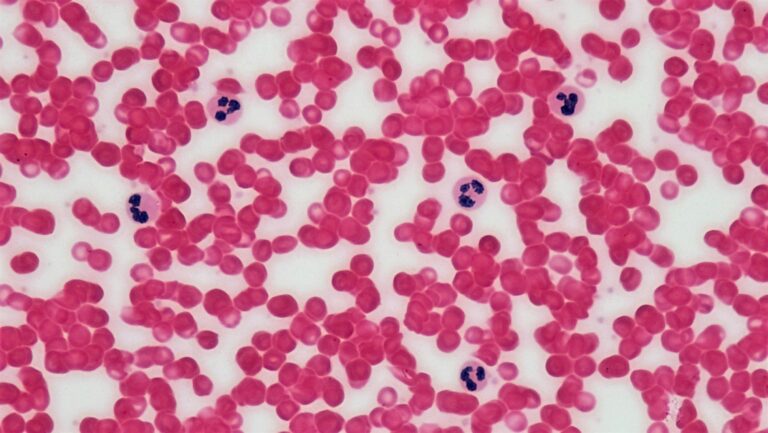

1) Immunotherapy – life-saving yet complex

Checkpoint inhibitors have transformed the treatment landscape for many cancers. Some patients gain years of life, while others do not respond. A small number experience serious immune-related side effects, such as myocarditis, pneumonitis, and colitis. There are also rare but documented fatalities in trials and monitoring databases. The numbers are small compared to overall use, but the harms are significant, which is why guidelines, monitoring, and early management protocols are necessary.

There is another subtlety we often overlook in headlines: the gut microbiome. Observational studies and mechanistic research suggest that antibiotics given around the start of PD-1 therapy can worsen outcomes, likely due to disrupting microbial species associated with better responses. It’s not a rule, but it’s an important signal. Many oncology teams are now more cautious with antibiotics around the start of immune checkpoint inhibition.

As a patient, I understand that hope and humility must coexist. I want access to the drug that might save my life while ensuring my clinical team focuses on detecting side effects early, respects the microbiome, and engages in honest discussions about trade-offs.

2) AI and algorithms – faster isn’t always fairer

I am excited about AI in healthcare. However, we’ve already seen how a commonly used risk algorithm inadvertently incorporated racial bias by using healthcare spending as a proxy for illness. This led to Black patients receiving less additional care despite the same risk scores. This was not malicious; it was a design choice that exacerbated inequity. Fixing it was simple once it was exposed: change the target to clinical need instead of spending. But this incident perfectly illustrates the modern “glow-in-the-bone” mentality. New does not mean neutral; new must be scrutinised.

If an algorithm influences my care, I want to understand what it optimises and who validated it across diverse populations. This is not anti-innovation; it supports safety.

3) Wellness fads – the risks of medical cosplay

In non-hospital settings, “miracle” drips and devices have become common. Some clinics market ozone therapy as a cure-all, but the US FDA has clearly warned that ozone is a toxic gas and that its safety or effectiveness for treating diseases is unproven. Both consumer and professional advisories have targeted unapproved ozone devices marketed to “clean” CPAP machines. It’s not excessive to ask for evidence; it’s an ethical requirement.

NAD+ infusions are another example. I appreciate the science of cellular metabolism and take supplements supported by research. However, claims that NAD+ IVs cure addiction or significantly reverse aging are, at best, unproven. There have been reports from UK clinics making sweeping claims that exceed the data. Promising treatments must undergo trials, and bold claims require solid proof.

My position is clear: use supportive therapies that have clinical guideline support when available, or at least therapies with plausible mechanisms and early human studies, in an adjunctive role with informed consent. Do not sell hope in a bag. Avoid using dangerous gases just because they’re trendy.

The integrative middle – where I choose to stand

When I was told in late 2024 that my condition was inoperable and incurable, I chose to take an active role in my care. I underwent chemotherapy and immunotherapy whilst creating an evidence-aware supportive plan that included diet, exercise, sleep, stress management, and selected adjuncts. Some adjuncts have guideline support in specific situations. For instance, photobiomodulation has recommendations from MASCC-ISOO for preventing and treating oral mucositis in defined contexts. These protocols are not just “wellness vibes”; they are systematic, dose-defined interventions supported by RCTs.

Regarding nutrition, I prefer a keto-vegetarian and low ultra-processed diet, but I emphasise the basics. The ESPEN guideline stresses early detection and treatment of malnutrition and metabolic issues during cancer care. Stability in weight, adequate protein, and individualised plans matter more than any social media debate. If a patient expresses interest in trying intermittent fasting during chemotherapy, I review the evidence with them. There are intriguing early signals for feasibility and tolerability, but it is not a one-size-fits-all prescription.

Integrative oncology isn't lacking in rigor. When done correctly, it actually requires more rigor since supportive measures are layered over conventional treatments. Careful monitoring for interactions, timing, and risks is essential. This is the balance I maintain: adjuncts that provide help without interfering.

The governance piece – progress with a brake pedal

One reason the mistakes of the 1950s faded is that we developed systems to catch harm sooner. Pharmacovigilance – the science of identifying, assessing, understanding, and preventing adverse effects – ensures that drugs and devices are monitored post-trial. In the EU, the EMA’s PRAC monitors safety signals and can enforce risk minimisation actions. The system isn’t perfect, but it exists to prevent the mistakes of the past from reoccurring.

The appropriate approach is to document adverse events, promote Yellow Card reporting in the UK, monitor for safety signals, and withdraw anything that fails to demonstrate benefit or poses unacceptable risk. Progress requires both acceleration and caution.

What future clinicians may criticise us for

It’s almost certain that future generations will look back at something we do now in hospitals and wellness settings and react with disbelief. My predictions include:

- Overusing imaging on healthy individuals with whole-body scans and incidental findings that trigger unnecessary anxiety and procedures with little benefit.

- Algorithmic shortcuts that appear efficient in dashboards but embed bias on a larger scale.

- Boutique infusions marketed with celebrity appeal and lacking solid outcome data.

Yet, I also believe that future clinicians will commend much of what mainstream oncology is doing today – from targeted agents that spare healthy tissue to safer, better-imaged radiation therapy – and what careful integrative practices offer, like exercise prescriptions, nutrition care plans, and evidence-based mind-body therapies that address anxiety and sleep issues in cancer.

The patient playbook – questions I wish I’d asked sooner

Justification – Why this test or treatment for me, now? What change will it bring? If it won’t change anything, can we skip or delay it?

Dose and duration – If imaging is necessary, can we minimise the dose? Is ultrasound or MRI an alternative? What dose benchmarks does this center follow?

Side effects and signals – With immunotherapy, what early signs of trouble should I report between week 1 and week 6? How will we manage them?

Antibiotics and timing – If I need antibiotics near the start of ICI therapy, how can we minimise disruption to my microbiome while treating the infection safely?

Algorithms in the room – Are any risk tools or AI systems involved in my care? What are they designed to optimise and how have they been evaluated for bias?

Integrative adjuncts – For each adjunct I’m considering, what is its guideline status, the quality of evidence, the dosing schedule, and the risk of interactions with my current treatment? If there’s no guideline or human data, why are we using it?

Reporting – If I experience an adverse effect, whether from hospital treatment or a supplement, how can we report it to improve care for future patients?

The point

The goal isn’t to criticise the past; it’s to recognise the pattern – where belief has outpaced safety – and to choose differently. Conventional medicine can save lives and still make mistakes. The same is true for integrative care. The aim shouldn’t be to take sides; it should be to use evidence as a guide and ethics as a safeguard.

Because somewhere right now, a well-meaning doctor is using a “miracle” machine. Somewhere, a wellness clinic is marketing a miracle in a bag. And somewhere, a patient like me is trying to survive long enough for the next genuine breakthrough in medicine to arrive. Let's ensure we can still recognise ourselves when the next photograph is taken.

References

- Kopp H. Radiation damage caused by shoe-fitting fluoroscope. British Medical Journal. 1957. Full text PDF: https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/2/5057/1344.full.pdf

- Lewis L, Caplan PE. The shoe-fitting fluoroscope as a radiation hazard. California Medicine. 1950. Full text: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1520288/

- Oak Ridge Associated Universities – Shoe-Fitting Fluoroscope museum notes – history, regulation timeline. https://www.orau.org/health-physics-museum/collection/shoe-fitting-fluoroscope/index.html

- Radithor – Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity – history and documented harm. https://www.orau.org/health-physics-museum/collection/radioactive-quack-cures/pills-potions-and-other-miscellany/radithor.html

- Eben Byers – historical summary of radium poisoning. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eben_Byers

- CDC – ALARA principle – radiation safety basics. https://www.cdc.gov/radiation-health/safety/alara.html

- ICRP Publication 154 – optimisation of radiological protection in medical imaging. https://www.icrp.org/publication.asp?id=ICRP+Publication+154

- StatPearls – Radiation Safety and Protection – overview of ALARA in clinical practice. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557499/

- NIH Research Matters – Radiation from CT scans and cancer risks – 2025 analysis summary. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/nih-research-matters/radiation-ct-scans-cancer-risks

- JAMA Internal Medicine – Projected Lifetime Cancer Risks From Current CT Use – Smith-Bindman et al, 2025. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2832778

- National Cancer Institute – CT Scans and Cancer Fact Sheet – risk, justification and dose reduction. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/diagnosis-staging/ct-scans-fact-sheet

- Wang DY et al. Fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors – systematic review and meta-analysis. (BMJ/oncology meta-analysis on PubMed summary page). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30242316/

- Fujiwara Y et al. Treatment-related adverse events including fatal toxicities with ICIs – updated evidence. The Lancet Oncology, 2024. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanonc/article/PIIS1470-2045%2823%2900524-7/abstract

- Routy B et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1 based immunotherapy – antibiotics associated with poorer response. Science, 2018. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aan3706

- Poizeau F et al. The association between antibiotic use and outcomes with ICIs – review of observational data. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9086805/

- Obermeyer Z et al. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science, 2019. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aax2342

- PubMed summary of Obermeyer et al. Science 2019 – algorithm bias details. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31649194/

- FDA – consumer update on ozone and UV devices marketed to clean CPAPs – evidence and safety concerns. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/do-you-need-device-claims-clean-cpap-machine

- EPA – ozone generators sold as air cleaners – health concerns and device limits. https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/ozone-generators-are-sold-air-cleaners

- FDA – recall information and safety concerns amplified by ozone use for CPAP devices. https://www.fda.gov/safety/recalls-market-withdrawals-safety-alerts/philips-issues-recall-notification-mitigate-potential-health-risks-related-sound-abatement-foam

- MedTech Dive summary – FDA warning letters to ozone CPAP cleaner marketers. https://www.medtechdive.com/news/fda-warning-letter-ozone-cleaner-cpap/726172/

- The Guardian – investigative reporting on NAD+ infusions and unproven addiction claims in UK clinics. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2025/feb/23/its-not-ethical-and-its-not-medical-how-uk-rehab-clinics-are-cashing-in-on-nad

- The Guardian – commentary on NAD boosters and anti-ageing claims – evidence gap. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/commentisfree/2025/apr/02/nad-boosters-what-are-they-do-they-work-celebrity-treatments

- MASCC-ISOO photobiomodulation guideline materials – evidence summary. https://mascc.org/resources/mascc-guidelines/

- MASCC-ISOO 2019-2020 photobiomodulation guideline slide set – recommendation details. https://assets.make.org/assets/media/events/5bfa354d-cd63-401c-9ea2-84a8b805521c/panoramic/1755698405080-Mucositis_Guidelines_Photobiomodulation_Doc–1-.pdf

- BMJ Open 2024 – photobiomodulation to prevent oral mucositis – protocol and MASCC references. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/14/10/e088073

- ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. https://www.espen.org/files/ESPEN-Guidelines/ESPEN_guidelines_on_nutrition_in_cancer_patients.pdf

- Integrative oncology – CA Cancer Journal for Clinicians overview of evidence-based integrative strategies. https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.3322/caac.21706

- Integrative review – intermittent fasting during chemotherapy – feasibility and signals, need for larger trials. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10715290/

- WHO – pharmacovigilance definition and purpose. https://www.who.int/teams/regulation-prequalification/regulation-and-safety/pharmacovigilance

- WHO – post-market surveillance overview. https://www.who.int/teams/regulation-prequalification/incidents-and-SF/post-market-surveillance

- EMA – Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) – role. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/committees/pharmacovigilance-risk-assessment-committee-prac

- UK MHRA overview of pharmacovigilance monitoring. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5feefb56d3bf7f089a791a2c/Pharmacovigilance___how_the_MHRA_monitors_the_safety_of_medicines.pdf

- ASCO-SIO and related integrative guidance summaries – exercise, mind-body and supportive measures during and after treatment. https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/EDBK-25-471734

Subscribe to stay connected