When I was first told I had incurable cancer, every conversation focused on the tumor. Cut it, poison it, starve it. It took me months to realise something else mattered just as much: the power plants inside my healthy cells, the mitochondria. When they are active, metabolism runs smoothly, immune cells function well, and the body’s stress signals calm down. When they are inactive, chaos spreads. Energy crashes, inflammation rises, and cancer thrives.

This piece aims to shift the focus back to mitochondria, explaining in simple terms how they affect cancer metabolism, why tumors often switch from clean energy to dirty glycolysis, and what the evidence says about practical ways to support mitochondrial function alongside standard treatment. I will share parts of my own journey, but the main foundation here is science. Each claim includes a full link so you can verify the source.

Part 1 – The energy shift cancer exploits

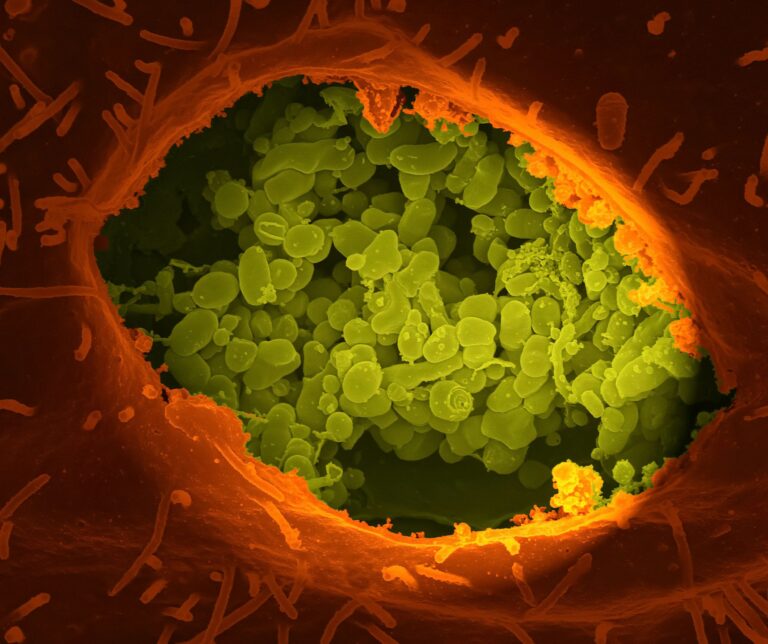

Many cancers change their energy strategy. Instead of fully burning glucose in mitochondria, they ferment it into lactate even when oxygen is available. This is known as the Warburg effect or aerobic glycolysis. It is not efficient, but it is quick and helps tumors grow, create biomass, and survive stress.

Here’s a clear overview of the Warburg effect and why cancers increase glucose uptake and lactate production:

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4783224/

For therapeutic strategies targeting the Warburg effect, check this background:

- https://www.nature.com/articles/aps201647

Tumors do not all behave the same way. Some maintain functional mitochondria, while others suppress them. Classic tumor suppressors like p53 play a crucial role in regulating glucose transporters, pyruvate routing, and antioxidant systems that determine whether cells burn cleanly or ferment:

- https://www.nature.com/articles/emm2016119

That sets the stage. If cancer shifts metabolism toward glycolysis, a sensible counter-move is to push metabolism back toward the mitochondria without harming healthy tissues. The rest of this article looks at evidence-based tools that may encourage this shift.

Part 2 – A quick primer on the mitochondrial gate – the PDH-PDK axis

Pyruvate Dehydrogenase (PDH) is the critical gate that moves carbons from glycolysis into the mitochondrial TCA cycle. Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinases (PDKs) add a phosphate to PDH, turning that gate off. Many tumors increase PDK levels to keep pyruvate out of mitochondria and maintain glycolysis.

For a review of mitochondrial metabolism and cancer treatments, see this:

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12319113/

If you inhibit PDKs, you can reactivate PDH, push pyruvate into mitochondria, and reduce lactate buildup. That’s why researchers are interested in dichloroacetate (DCA).

A 2025 review discusses DCA as a pan-inhibitor of PDK, decreasing lactic acid and improving oxidative phosphorylation:

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40922281/

Mechanistic data shows DCA reduces PDK levels in an isoform-dependent manner:

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34445316/

In melanoma cell lines, DCA reduced proliferation by reprogramming metabolism and showed synergy with other metabolic agents:

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35409102/

These findings are preclinical or early-stage and do not prove benefits in humans with cancer. However, they do highlight an important biochemical lever: the PDH-PDK axis, which controls how much fuel enters mitochondria.

Part 3 – Lifestyle levers that pressure metabolism toward clean burn

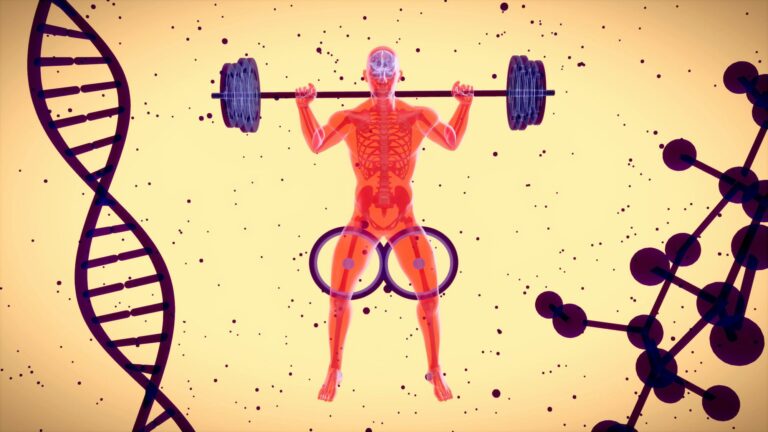

3.1 – Exercise and mitochondrial biogenesis

Exercise sends a strong signal to mitochondria. It boosts biogenesis programs and improves mitochondrial quality control. A 2025 meta-analysis showed a significant increase in PGC-1α expression, the transcriptional coactivator often linked with mitochondrial biogenesis, after endurance training:

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40459444/

The PGC-1α story is complex. Some mouse models indicate that exercise-induced mitochondrial biogenesis can still happen even when skeletal muscle PGC-1α is absent, meaning other pathways may step in. The main point remains: exercise increases mitochondrial capacity through multiple overlapping routes:

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22848618/

3.2 – Fasting and metabolic switching

Short fasting periods or fasting-mimicking diets can lower circulating glucose and insulin-like growth factor 1, increase fatty acid use, and activate cellular programs that support mitochondrial maintenance and stress resistance. Reviews summarise initial clinical and strong preclinical signals that fasting can make tumor cells more vulnerable while protecting normal cells:

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11591922/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10719255/

It’s important to note that fasting during treatment needs clinical guidance, especially for underweight or frail patients. Strategies must be tailored to individual needs.

3.3 – Ketogenic patterns and carbohydrate restraint

Ketogenic diets are sometimes used to reduce glycolytic activity and lactate levels, aiming to challenge tumors that rely heavily on glucose. The clinical evidence is mixed and still evolving. An umbrella review found moderate to high-quality evidence for some cardiometabolic benefits:

- https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-023-02874-y

Cancer-specific systematic reviews and meta-analyses are emerging, with varied designs and outcomes, which are useful for generating hypotheses rather than providing definitive guidance:

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12313497/

Personally, a low-processed, high-fiber, keto-leaning vegetarian diet has worked for me. It emphasises whole-food fats, non-starchy vegetables, fermented foods, and careful protein intake while monitoring body weight and labs.

Part 4 – Adjuncts that intersect with mitochondrial function

4.1 – Metformin – an old drug with metabolic effects

Metformin activates AMPK and influences multiple aspects of metabolic reprogramming. Preclinical and observational clinical data suggest it can affect tumor cell energy use, reduce insulin signals, and interact with immunometabolism. It is not a cure-all, and the clinical evidence varies across different cancers, but it plays an important role in mitochondrial function:

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10998183/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9048115/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10286395/

4.2 – Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) – oxygen as a metabolic tool

HBOT increases the amount of dissolved oxygen in plasma. In theory, this can reduce tumor hypoxia, a major factor driving glycolysis, angiogenesis, and treatment resistance. The practical use in oncology is still under investigation. Reviews suggest HBOT is beneficial and safe for various complications related to radiation and surgery and is being studied for its direct effects on tumors.

For a review of HBOT as an adjunct for managing complications of solid tumors, see this:

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11943617/

For broader investigative directions:

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12183197/

Regarding head and neck cancer dysphagia after radiation, evidence is inconsistent and more trials are needed:

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38704813/

In my experience, HBOT has aided in recovery and overall well-being. I view it as a supportive therapy rather than a standalone treatment for cancer.

4.3 – Photobiomodulation (red and near-infrared light)

Photobiomodulation (PBM) uses specific wavelengths to interact with cytochrome c oxidase and other molecules, adjusting mitochondrial respiration and redox signaling. In oncology, PBM is recognised for preventing oral mucositis and providing supportive care, with growing research into its broader roles.

For a 2024 systematic review of PBM in oncology supportive care, see this:

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11493773/

For another 2024 review on PBM as supportive care for cancer patients:

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11633914/

A word of caution: cellular studies have shown effects can vary based on context. One in vitro study suggested PBM could reduce the redox state in normal tissue while increasing glycolysis in oral cancer cells. This doesn’t directly imply clinical harm, but it serves as a reminder to follow oncology-informed protocols:

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8367241/

4.4 – Mitochondrial biogenesis, quality control, and nutrients

Mitochondrial health depends on biogenesis, mitophagy, and the dynamics of fusion-fission. Reviews discuss how endurance exercise, caloric cues, and different stressors can coordinate these programs:

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8533934/

Nutrients typically considered for mitochondrial support include magnesium, CoQ10, alpha-lipoic acid, L-carnitine, riboflavin, and niacin-derived NAD precursors. These are theoretically plausible, but clinical evidence varies widely. The hype surrounding NAD+ in the media should be distinguished from careful clinical use in oncology, as some journalism has called out overclaiming in private clinics:

- https://www.theguardian.com/society/2025/feb/23/its-not-ethical-and-its-not-medical-how-uk-rehab-clinics-are-cashing-in-on-nad

I maintain an evidence-first approach here. Nutrition can aid cellular energy but should be integrated with professional guidance and actual biomarkers rather than trends.

Part 5 – Pulling it together – a practical mitochondrial strategy

This is the simple mitochondrial checklist I wish I had from the start. It is not a strict guide because every patient is unique, but it reflects what the evidence and my experiences support.

1 – Build the base

Focus on whole foods, unprocessed items with enough protein, colorful non-starchy vegetables, and high natural fiber. This supports the microbiome and the production of short-chain fatty acids that reduce inflammation and nourish colon cells, benefiting mitochondria.

Caloric intake is important in cancer. Any carbohydrate restraint or fasting approach must preserve lean mass and clinical stability.

2 – Move every day

Make aerobic exercise and gentle strength work a priority. The aim is to increase mitochondrial density and insulin sensitivity, not just to push personal limits. The signaling for biogenesis responds positively to dose and involves multiple pathways:

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40459444/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22848618/

3 – Consider structured metabolic stressors

Engage in time-restricted eating or short fasting-mimicking periods with clinical oversight. Potential benefits may include reduced insulin-IGF signaling and improved treatment tolerance:

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11591922/

4 – Discuss metabolic adjuvants with your team

Metformin, DCA, or ketogenic phases are not one-size-fits-all. There is a mechanistic basis for these treatments, but the human evidence is cancer-specific and varies. Decisions need to be made in a clinical context that considers tumor type, treatment plan, comorbidities, and individual goals:

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10998183/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40922281/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12313497/

5 – Use supportive modalities when appropriate

Utilise HBOT for specific indications and recovery while being aware of the limitations of the data:

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11943617/

Consider photobiomodulation for oral mucositis and other symptom support, using oncology-informed protocols:

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11493773/

6 – Track what matters

Monitor basic labs such as fasting glucose, HbA1c, lipids, and CRP.

Look at functional markers like perceived energy, sleep patterns, heart rate variability (HRV), resting heart rate, and exercise tolerance.

Check treatment-aligned metrics, whatever your oncology team uses to track disease and toxicity.

Part 6 – My lived experience – flipping the switch back on

When I focused on my mitochondria, I didn’t strive for perfection. Instead, I established a routine. I included daily movement, a fiber-rich keto-leaning vegetarian diet, fermented foods, structured breathwork, and short fasts when safe. I also used HBOT and gentle red light for recovery. I carefully reviewed off-label medications for interactions. I noticed changes in my energy and inflammation markers first; my life improved, then I realised I could handle more challenges.

Do I believe any single approach cured me? No. Do I think my mitochondria were a vital part of my strength and resilience? Yes.

The key takeaway is this: cancer is not just a problem of cells. It is an ecosystem issue. Mitochondria lie at the heart of that ecosystem, transforming oxygen, food, and movement into clean energy and calm signals. Each day you activate them is a day you make it a bit tougher for chaos to thrive.

Key takeaways

Many tumours favour glycolysis over mitochondrial oxidation – the Warburg effect. Pressuring metabolism back toward the mitochondria is a rational adjunct goal.

The PDH-PDK gate is a central lever. DCA inhibits PDKs and reopens mitochondrial carb entry in preclinical work – promising mechanism, mixed early data, not a proven therapy.

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40922281/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34445316/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35409102/

Exercise, fasting patterns, and possibly ketogenic phases can nudge mitochondria toward clean burn. Personalisation and safety are non-negotiable.

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40459444/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11591922/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12313497/

Metformin intersects several reprogramming nodes. HBOT and PBM are emerging supportive tools – useful for complications and recovery, with ongoing research for direct anti-tumour roles.

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10998183/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11943617/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11493773/

The future is precision metabolism – matching diet, movement, and adjuncts to individual tumour biology and whole-body context.

References

- The Warburg Effect – how it benefits cancer cells

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4783224/ - Therapeutic targeting of the Warburg effect

https://www.nature.com/articles/aps201647 - ROS homeostasis, p53 and metabolic control

https://www.nature.com/articles/emm2016119 - Mitochondrial metabolism and cancer – therapeutic innovation

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12319113/ - DCA as a pan-inhibitor of PDK – metabolism and OXPHOS

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40922281/ - DCA reduces PDK abundance – isoform-dependent mechanisms

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34445316/ - DCA reprograms melanoma metabolism – synergy data

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35409102/ - Exercise-induced mitochondrial signalling – meta-analysis

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40459444/ - Exercise – biogenesis even without skeletal muscle PGC-1α

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22848618/ - Fasting as adjuvant therapy – mechanisms and early data

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11591922/ - Fasting regulates mitochondrial function – lncRNA pathway study

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10719255/ - Ketogenic diet – umbrella review of outcomes in general populations

https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-023-02874-y - Ketogenic diet in cancer – systematic review and meta-analysis

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12313497/ - Metformin – anticancer agent and adjuvant review

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10998183/ - Metformin – metabolic reprogramming mechanisms

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9048115/ - Metformin and cancer hallmarks

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10286395/ - HBOT for managing cancer treatment complications

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11943617/ - Exploring HBOT to improve tumour hypoxia and transport

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12183197/ - HBOT for head and neck dysphagia post-radiation – inconsistent evidence

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38704813/ - PBM in oncology – systematic review

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11493773/ - PBM as supportive care for cancer patients

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11633914/ - PBM and redox – context-dependent cellular effects

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8367241/ - Molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8533934/ - General overview – therapeutic targeting of aerobic glycolysis

https://www.nature.com/articles/aps201647

Subscribe to stay connected