The day I named my tumour Dave, I promised myself I would not fight in the dark. Nutritional ketosis became one of the tools that cleared the battlefield. That’s why this study caught my attention; it asks a rare but straightforward question: what happens to key hormones when people in ketosis deliberately turn it off for a while and then back on again? There’s no hype, just data that helps patients and doctors make better choices.

The paper in one paragraph

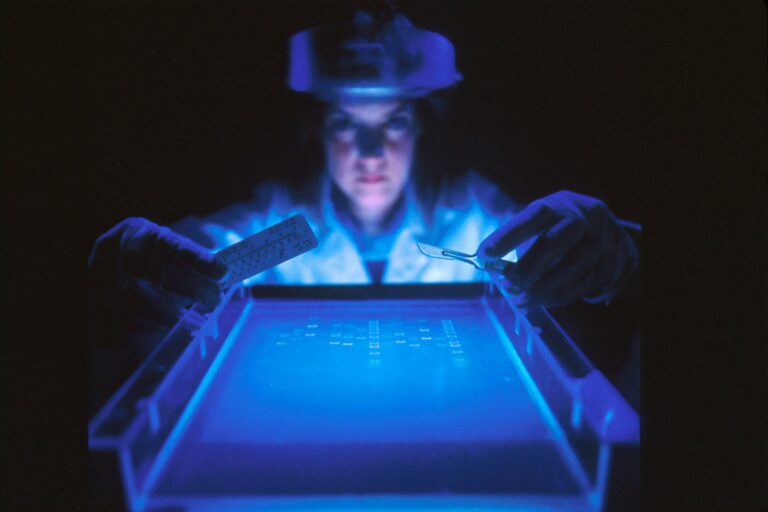

Dr. Cooper and her colleagues conducted an open-label, three-phase crossover study with ten healthy, lean, premenopausal women who had been in nutritional ketosis for several years. Each participant spent 21 days in habitual ketosis, followed by 21 days of deliberate ketosis suppression, and then 21 days back in ketosis. During ketosis suppression, sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) decreased significantly, and this decrease tracked with signs of increased insulin exposure and related metabolic changes. When participants returned to ketosis, SHBG levels rose again. The authors explain why this is important for hormone health, cancer risk, and treatment decisions.

Key results – translated

– SHBG decreased during the suppression of ketosis and returned to normal after. The mean SHBG fell from about 108 nmol/L during habitual ketosis to around 73 nmol/L when ketosis was suppressed, then bounced back to roughly 112 nmol/L when ketosis resumed. That on-off-on pattern is the kind of biological signal that clinicians take seriously.

– SHBG levels moved inversely with insulin exposure and other metabolic markers. Lower SHBG matched with higher insulin and HOMA-IR, higher glucose-ketone index, increased leptin and IGF-1, and elevated GGT. In simple terms, as the metabolic environment became more “insulin-dominated,” SHBG levels dropped.

– Other sex hormones did not change significantly in this small group. Oestrogen, progesterone, testosterone, LH, and FSH mostly stayed steady across phases, aside from expected menstrual-phase variations.

Why SHBG matters for cancer conversations

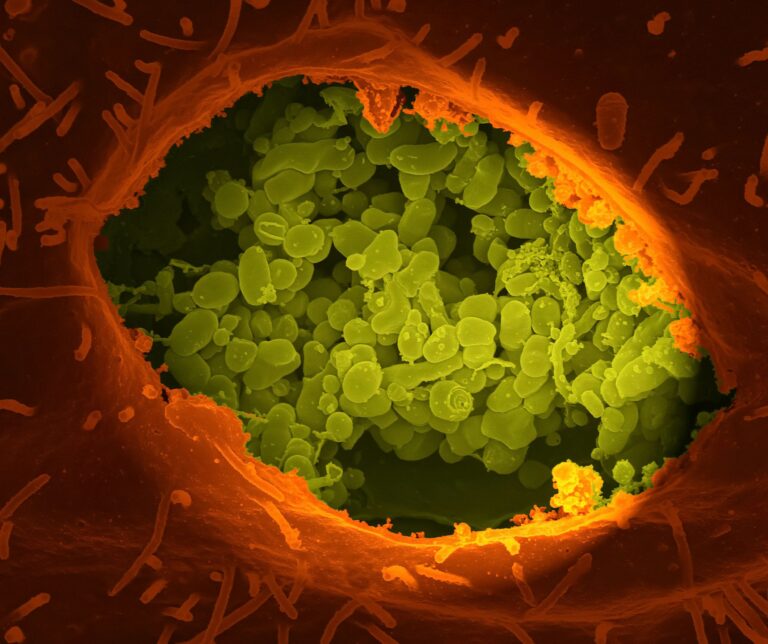

SHBG is a protein made by the liver that binds sex hormones. It’s not just a passive transport tool. Lower SHBG is consistently linked to insulin resistance and negative blood sugar markers, which is one reason metabolic clinicians pay attention to it.

For hormone-sensitive cancers like breast cancer, lower circulating SHBG has been associated with a higher risk in observational studies, particularly after menopause. The cause is complex and still debated, but this risk signal appears frequently.

Combining these facts gives a clinically relevant picture: if turning off ketosis worsens insulin signalling and correlates with lower SHBG, then the metabolic and hormone environment shifts in a direction that most oncologists would prefer to avoid, especially in patients for whom hormones and insulin-IGF-1 pathways are significant. This doesn’t turn keto into a cure, but it supports the case for metabolic maintenance as part of comprehensive cancer care.

How this mirrors my own experience

In case you’re new here, in October 2024 I was diagnosed with stage IV oesophageal adenocarcinoma. I undertook chemotherapy and immunotherapy (still ongoing as at time of writing), and I supported them with grounded, evidence-based metabolic strategies. I followed a ketogenic, plant-forward diet, tightly controlled refined carbs, and tracked my glucose and ketones, especially evening readings and the glucose-ketone index. When I strayed from that routine – due to travel, treatment days, or difficult times when my willpower succumbed to toast – my evening ketones dropped, and the GKI rose. Energy levels, appetite, and markers of inflammation reflected this change in ways I could sense and sometimes see in lab results. This study’s patterns on SHBG and insulin align with what my body has been telling me for months: consistency matters.

This is not a miraculous story; it’s about logistics.

Why Dr Cooper, Dr Seyfried, and the team deserve real credit

This study is not a flashy, one-off breakthrough. It carefully examines physiology across repeated phases, with meaningful biomarkers and a clear pathway that many clinicians can use. Dr Cooper’s group has consistently mapped how chronically low ketones from high insulin levels signal metabolic dysfunction long before standard labs indicate issues. Prof. Thomas Seyfried (he of DOAC fame and a contributor on this paper) has spent decades clarifying why metabolism is not a minor aspect in oncology but an essential factor that interacts with inflammation, hormones, and mitochondria. Together, this perspective helps move us past divisive diet arguments and into testable clinical actions.

Putting results in context – supportive, but balanced

– This study involved a small, healthy group. Ten lean women, already adapted to keto for years, provide a good model to isolate a signal. However, they are not equivalent to patients currently undergoing cancer treatment. We need to replicate these findings in larger, more diverse groups.

– SHBG serves as a proxy, not a definitive measure. While lower SHBG correlates with insulin resistance and, in some cases, increased breast cancer risk, it is not a switch you can flip to get or avoid cancer. It is a valuable indicator on the dashboard.

– The metabolic effects of keto are real and varied. Meta-analyses and controlled trials suggest ketogenic diets can reduce insulin and IGF-1 in many situations, though not every trial shows blood sugar improvements unrelated to weight changes. The principle remains: if your clinical goal is to reduce insulin-IGF-1 signalling, structured carbohydrate restriction is a valid option, but it should be implemented with professional guidance, especially in oncology.

Practical takeaways you can use this week

This is not medical advice. It’s what I would discuss with my own team if I were starting today.

1. Track what matters, not just what is easy. Evening beta-hydroxybutyrate and the glucose-ketone index are straightforward home checks that show the metabolic pressure insulin is exerting. Sustained low ketone levels should prompt a review of diet, sleep, stress, and activity levels.

2. Get a sensible lab panel. Besides standard tests, request fasting insulin, SHBG, IGF-1, and liver enzymes like GGT if SHBG is decreasing while insulin and IGF-1 increase; the overall trend is more important than any single result.

3. Match the tool to the tumour. For hormone-sensitive cancers, maintaining metabolic and hormone balance can be very beneficial. For other types, it is still helpful for overall resilience and treatment tolerance, but the benefits vary by individual biology. Keep your oncologist informed and document everything.

4. Prioritise consistency over perfection. The study’s on-off-on design shows that the body responds quickly to repeated actions. Perfection isn’t necessary; instead, focus on a sustainable routine during scans, steroids, antibiotics, and life in general.

5. Use nutrition to decrease insulin-IGF-1 signalling wisely. This means incorporating quality protein to maintain lean mass, fibre-rich low-glycemic plant foods, healthy fats, and smart meal timing. Some patients may benefit metabolically from a ketogenic approach, while others may do well simply by cutting refined sugars and narrowing eating windows. Both methods achieve similar goals.

How this fits with standard care

I underwent chemotherapy and immunotherapy. I am surviving due to science and determination. Nutrition and metabolic care complemented my oncology treatment, rather than replaced it. Studies like this assist teams in aligning dietary choices with the realities of metabolic and endocrine function instead of leaving patients to figure it out at 2 a.m. on Google. The goal is not to win a diet debate. The aim is to change the internal environment in a way that helps treatments work better and makes patients feel more human.

What to ask your team

– Would tracking evening ketones and GKI be valuable in my case, or is there a better metric for me right now?

– Can we include fasting insulin, SHBG, and IGF-1 in my following blood tests and review the pattern over time?

– If I adopt a ketogenic or lower-carb diet, how can we protect lean mass and monitor for issues like fatigue or nutrient deficiencies?

– How does my tumour biology interact with insulin-IGF-1 signalling, and does that influence our nutritional focus during treatment cycles?

A word of thanks

Credit where it’s due. Thank you to Dr Isabella Cooper and her team for designing a study that answers a practical clinical question. And, thank you to Prof. Thomas Seyfried for championing metabolic considerations when they were unpopular.

This type of work improves multidisciplinary care rather than complicating it.

References

- Cooper ID, Petagine L, Soto-Mota A, Duraj T, Seyfried TN, Lee DC, et al. Ketosis suppression and ageing (KetoSAge): the effect of suppressing ketosis on SHBG and sex hormone profiles in healthy premenopausal women, and its implications for cancer risk and therapy. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2026 Jan 2. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/nutrition/articles/10.3389/fnut.2025.1731915/full

- Aroda VR, et al. Circulating sex hormone-binding globulin levels are associated with insulin resistance and glycaemic measures. BMJ Diabetes Research & Care. 2020. https://drc.bmj.com/content/8/2/e001841

- Daka B, et al. Inverse association between serum insulin and sex hormone-binding globulin in men and women. Endocrine Connections. 2013. https://ec.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/ec/2/1/18.xml

- Dimou NL, et al. Sex hormone-binding globulin and risk of breast cancer: Mendelian randomization analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2019. https://academic.oup.com/ije/article-abstract/48/3/807/5506081 and open-access summary: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6659370/

- Zhao S, et al. Low SHBG predicts unfavourable prognosis in breast cancer. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2024. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10921478/

- Yuan X, et al. Effect of the ketogenic diet on glycaemic control and insulin resistance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition & Diabetes. 2020. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41387-020-00142-z

- Rajakumar G, et al. Effect of ketogenic diets on insulin-like growth factor-1 in humans: systematic review. Ageing Research Reviews. 2024. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1568163724003490 PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39396675/

- Merovci A, et al. Weight-maintaining ketogenic diet and glycaemic control. BMJ Diabetes Research & Care. 2024. https://drc.bmj.com/content/12/5/e004199

- Tsujimoto T, et al. Hyperinsulinaemia and cancer mortality in non-obese, non-diabetic adults: a prospective cohort. Oncotarget. 2017. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5435954/

Notes and disclaimers

This blog is educational and reflects the study’s data plus wider literature. It is not a prescription, and it is not a replacement for oncologist-led care. Nutritional strategies in cancer should be personalised, monitored and adjusted with your clinical team.

Subscribe to stay connected