They told her the glow in her bones was “healthy energy.” Years later, her jawbone crumbled in her hands.

That photograph, the one circulating on social media, is a warning disguised as nostalgia. We celebrate progress, but progress comes with a cost. My own cost arrived in October 2024 with the diagnosis of “Stage IV oesophageal adenocarcinoma.” I pursued the best conventional care available, which included chemotherapy and later immunotherapy. I also added supportive and complementary strategies. This was not a fight against medicine. It was a request for medicine plus: using evidence when possible, exploring with curiosity everywhere else, and being honest about trade-offs.

This post will clearly show where chemotherapy can cure, where it usually cannot, how oesophageal cancer fits into this, and why life after treatment needs more than hope. This is not medical advice. It is a guide you can bring to your clinic and discuss with your care team.

Where chemotherapy can be curative

Some cancers respond well to cytotoxic chemotherapy as a curative tool. Cure means complete eradication and long-term survival for a significant number of patients.

– Testicular cancer: Platinum-based treatments cure most patients, even those with metastatic disease. Five-year survival rates in high-income countries exceed 95 percent due to chemosensitivity and modern treatment pathways. See the National Cancer Institute’s treatment summaries for context and protocols: https://www.cancer.gov/types/testicular/patient/testicular-treatment-pdq [1]

– Hodgkin lymphoma: Combination chemotherapy, typically ABVD or related protocols, cures most patients. The NCI’s PDQ details multi-modal options and long-term control rates. https://www.cancer.gov/types/lymphoma/hp/adult-hodgkin-treatment-pdq [2] https://www.cancer.gov/types/lymphoma/patient/adult-hodgkin-treatment-pdq [3]

– Aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas, especially diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): R-CHOP and newer variants cure a large number. Health-professional PDQ pages outline standard curative treatments. https://www.cancer.gov/types/lymphoma/hp/aggressive-b-cell-lymphoma-treatment-pdq [4] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK66057/ [5]

– Several childhood blood cancers: Chemotherapy is essential for curing pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia, with modern protocols achieving high long-term survival rates. Refer to NCI pediatric PDQ resources: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/pdq/information-summaries/childhood-treatment [6]

These examples are important because they protect us from two mistakes. First, the mistake of cynicism, which claims that chemotherapy never cures. Second, the mistake of assuming that what cures one cancer will cure all types.

Where chemotherapy is usually not curative on its own

For many solid tumors, particularly when they are metastatic, chemotherapy mainly helps shrink, slow, relieve, and provide time for other options. Language matters. Palliative does not mean useless. It focuses on goals of longevity and quality of life.

– Metastatic colorectal cancer: Systemic therapy improves survival and symptoms, but a cure is rare without potentially curable surgery for limited metastases. National and international summaries make this clear: https://www.cancer.gov/types/colorectal/patient/colon-treatment-pdq [7]

– Metastatic breast cancer: Generally not curable with available systemic treatments, though many live meaningful lives for years with sequential lines of therapy. The American Cancer Society is straightforward about this: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/treatment/treatment-of-breast-cancer-by-stage/treatment-of-stage-iv-advanced-breast-cancer.html [8]

– Lung cancer: Caution is essential. Limited-stage small-cell lung cancer may be treated with curative intent through chemotherapy and radiotherapy, but the NCI honestly states this is “curative in only a few.” Advanced non-small-cell lung cancer is typically not curable with chemotherapy. https://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/hp/small-cell-lung-treatment-pdq [9] https://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/hp/non-small-cell-lung-treatment-pdq [10]

– Pancreatic cancer: Systemic therapy can extend life and lessen symptoms in advanced cases, but a cure is rare outside resectable situations. Major guidelines confirm this: https://www.cancer.gov/types/pancreatic/patient/pancreatic-treatment-pdq [11]

– Prostate cancer: In metastatic hormone-sensitive disease, chemotherapy can offer survival benefits alongside androgen deprivation, but it is not curative in this metastatic stage. Guidelines and large trials agree on this. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/patient/prostate-treatment-pdq [12]

– Oesophageal cancer: This is the one that changed my life. The distinction here is clear. Curative intent usually requires multimodal therapy: surgery plus perioperative chemotherapy (like FLOT) or pre-operative chemoradiation followed by surgery (CROSS regimen). For stage IV disease, treatment is mainly palliative. Chemotherapy and immunotherapy can improve symptoms and survival, but a cure is rare. See PDQ, CROSS, FLOT, and UK patient guidance for details: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65900.1/ [13] https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1112088 [14] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanonc/article/PIIS1470-2045(15)00040-6/fulltext [15] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)32557-1/fulltext [16] https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/oesophageal-cancer/treatment [17]

These points are not value judgments. They simply define what to expect. If you are a patient or caregiver, understanding the real aim of your treatment – cure, control, or comfort – helps you plan effectively.

What chemo does under the hood

Chemotherapy attacks DNA or the machinery that divides cells to prevent multiplication. It does not come with GPS. Healthy cells that regenerate quickly suffer consequences: bone marrow, gut lining, hair follicles, and peripheral nerves. Some effects fade over time, while others can last.

– Immune suppression and infection risk: Neutropenia is a common and serious short-term effect. This is standard knowledge from the NCI and a reason for urgent care plans concerning fever. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/patient-education/chemo-and-you [18]

– Peripheral neuropathy: This is especially associated with oxaliplatin, paclitaxel, or vinca alkaloids. Systematic reviews highlight both its prevalence and the difficulty in treating it. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10757127/ [19]

– Cognitive effects: “Chemo brain” is a real issue for some patients. The NCI offers patient-friendly materials discussing the mechanisms and coping strategies. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects/memory [20]

– Therapy-related second cancers: While these numbers may be small, they are a genuine risk following certain agents and radiation, particularly therapy-related myeloid neoplasms. Refer to NCI and ACS resources. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/radiation/second-cancers-caused-by-cancer-treatment [21] https://www.cancer.org/cancer/survivorship/long-term-health-concerns/second-cancers-in-adults.html [22]

None of this is an argument against chemotherapy. It instead advocates for informed consent and long-term plans to restore what treatment depletes.

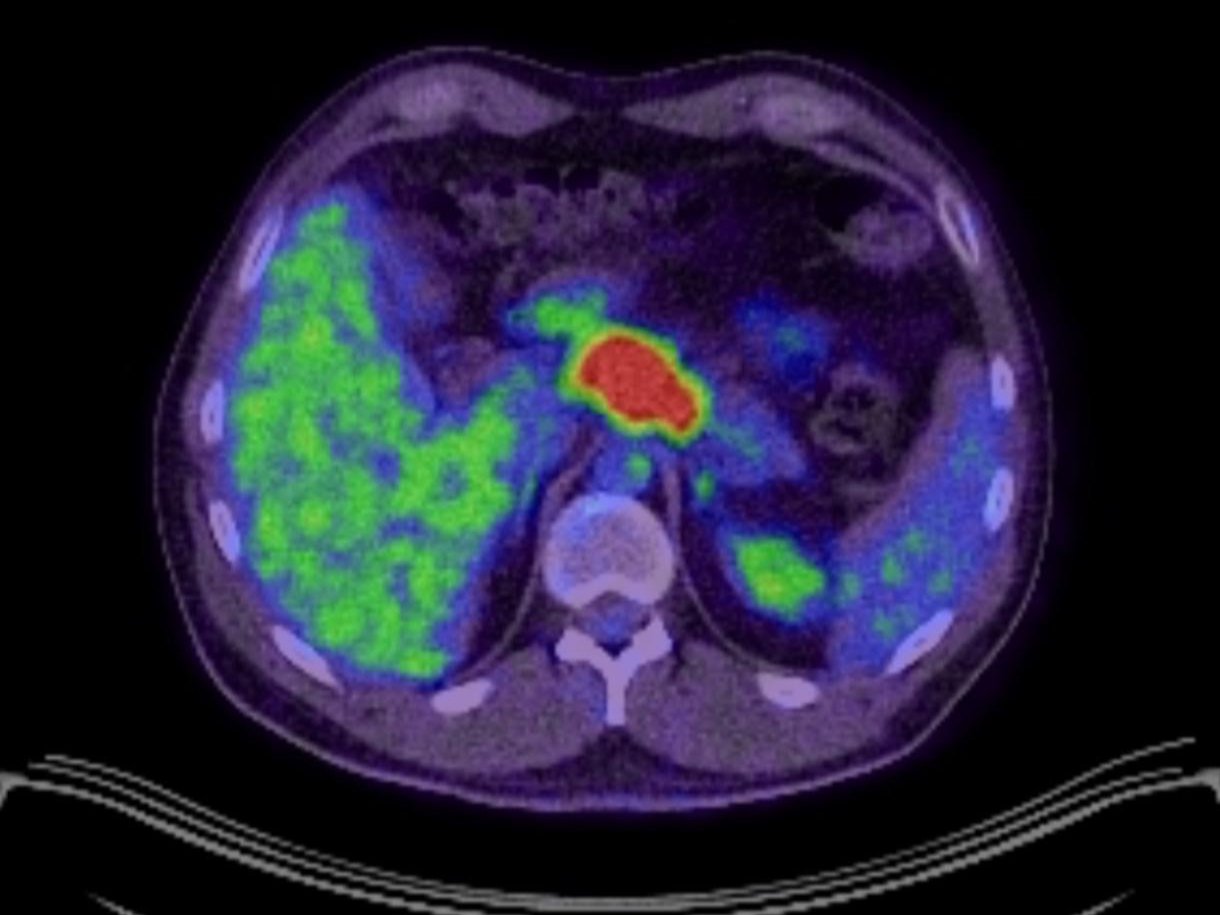

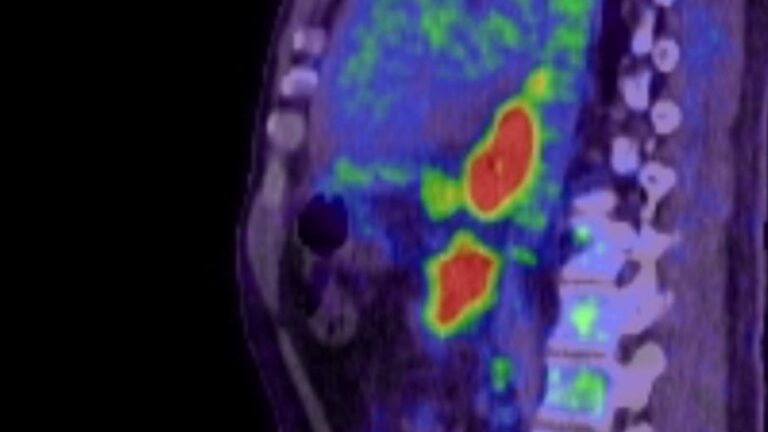

Scans, contrast, and cumulative load

I lost track of how many scans I had. CT scans, PET-CT scans, and contrasted studies. Each image provided a necessary insight. Two facts can coexist.

– Fact one: scans can save lives. When used properly, CT can replace invasive procedures, alter treatment plans, and accurately track responses. The FDA and ACR materials clearly outline the benefits: https://www.fda.gov/radiation-emitting-products/medical-x-ray-imaging/computed-tomography-ct [23] https://www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info/safety-xray [24] https://www.acr.org/News-and-Publications/Media-Center/2025/jama-ct-scan-radiation-study [25]

– Fact two: dose and contrast are significant. IoniSing radiation is not negligible. Typical effective doses are well documented by radiology societies and patient resources. We can make informed choices about imaging types and frequency. NICE in the UK sets standards for evaluating risk when using iodinated contrast for at-risk kidneys. The key takeaway is pragmatic: minimise unnecessary exposure, opt for MRI or ultrasound when possible, and evaluate contrast risks instead of reflexively avoiding them. https://www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info/safety-hiw_07 [26] https://www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info/bodyct [27] https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng148 [28] https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng148/resources/visual-summary-pdf-13551376429 [29] https://www.clinicalradiologyonline.net/article/S0009-9260%2820%2930630-9/fulltext [30]

A practical request for the clinic: for each proposed scan, ask how it will change our next steps and if there is a lower-radiation option that addresses the same question.

Why personal responsibility still matters after treatment

Chemotherapy and immunotherapy can clear the battlefield, but they don't rebuild what’s needed. Some of the toughest challenges after treatment – fatigue, low fitness, neuropathy, poor sleep, and high stress – demand active rehabilitation.

– Exercise and movement: The research on exercise in oncology is solid. A 2025 British Journal of Sports Medicine synthesis and recent systematic reviews link physical activity to better fatigue management, improved cardiorespiratory fitness, reduction in peripheral neuropathy symptoms, better sleep, and enhanced quality of life. While the exact prescription varies, the case for “some, most days” is strong. Ensuring safety means tailoring the plan to your diagnosis and treatment type. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/59/14/1010 [31] https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/bjsports/59/14/1010.full.pdf https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10757127/ [32] https://www.cochrane.org/evidence/CD015520_does-yoga-relieve-cancer-related-fatigue-people-cancer [33]

– Inflammation and gut health: Survivorship research links ongoing low-grade inflammation and gut microbiome disruptions to fatigue and slower healing. Multiple reviews highlight chemotherapy-related dysbiosis. Rebuilding gut health with fiber-rich, minimally processed food, appropriate probiotics, and time is helpful. The mechanisms are still being investigated, but this approach is sensible and low-risk. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7243601/ [34] https://theoncologist.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/onco.14354 [35]

– Sleep, stress, and load management: Simple, yet crucial. Lower your controllable toxic load. Prioritise sleep. Say no to some things while you heal.

This is where integrated approaches fit in. Not as a substitute for necessary treatment, but in addition to it, especially after treatment.

My lane, honestly

I was told my treatment was palliative. We crafted a protocol that combined conventional therapy with supportive, evidence-informed additions. I am transparent about chemotherapy’s role and its limitations in stage IV oesophageal adenocarcinoma. I also acknowledge how beneficial the “boring” practices proved – strength training when I could, maintaining healthy sleep habits, following a low-sugar, low-refined-carb diet, supporting mitochondrial health, caring for my microbiome, and responsibly using mistletoe therapy. Some of these have stronger evidence than others, but they all rest on a simple idea: if treatment is a storm, then recovery requires rebuilding what was lost.

A patient-first checklist you can use tomorrow

Bring this to your next appointment and adjust it for your situation.

1. Intent: Is my current treatment meant to cure, control, or relieve? If it’s a cure, what does success look like at 6, 12, and 24 months?

2. Oesophageal specifics: If your cancer is oesophageal and possibly resectable, ask if perioperative chemotherapy like FLOT or pre-operative chemoradiation followed by surgery is suitable. If stage IV, ask which systemic options best align with your subtype and PD-L1 or HER2 status, and clarify what realistic goals are. Bring the CROSS and FLOT information into the discussion if useful: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65900.1/ [13] https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1112088 [14] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanonc/article/PIIS1470-2045(15)00040-6/fulltext [15] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)32557-1/fulltext [16] https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/oesophageal-cancer/treatment [17]

3. Scan value: For each recommended scan, ask how the results will affect decisions. If the answer is “it won’t,” consider interval or type of scan. If contrast is needed, inquire how your kidney risk will be assessed. NICE provides a reasonable framework: https://www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info/safety-hiw_07 [26] https://www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info/bodyct [27] https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng148 [28] https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng148/resources/visual-summary-pdf-13551376429 [29]

4. Side-effect plan: What’s the plan for neutropenic fever, neuropathy, mouth sores, and diarrhea? Who can I contact at 2 a.m.? What gets me to the hospital quickly? Write it down. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/patient-education/chemo-and-you [18] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10757127/ [19]

5. Rebuild plan: Work on a staged return to movement. “Some, most days” is better than a heroic effort followed by burnout. Refer to the BJSM and systematic-review evidence if skepticism arises. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/59/14/1010 [31] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10757127/ [32] https://www.cochrane.org/evidence/CD015520_does-yoga-relieve-cancer-related-fatigue-people-cancer [33]

6. Data and decisions: If genomics or immunotherapy are options, ask how antibiotics, gut health, and timing might influence outcomes. Your care team will have information on emerging data to help you avoid mistakes.

7. Language audit: Avoid using the word “just.” “We can just watch and wait.” “It just buys time.” Both watching and waiting, and buying time are choices. Make them intentional.

Final thought

That photograph from the 1960s is not an argument against progress. It is a reminder of humility. Chemotherapy has saved millions of lives, yet it has also left many with significant challenges. My request to clinicians and patients is clear. Be truthful about the intent of treatment. Scan only when it will make a difference. Treat side effects as seriously as you treat tumors. And engage in the necessary, everyday work of rebuilding after treatment. That is how we honor progress without falling into the same pitfalls.

References

- National Cancer Institute. Testicular Cancer Treatment (PDQ) – Patient. https://www.cancer.gov/types/testicular/patient/testicular-treatment-pdq

- National Cancer Institute. Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment (PDQ) – Health Professional. https://www.cancer.gov/types/lymphoma/hp/adult-hodgkin-treatment-pdq

- National Cancer Institute. Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment (PDQ) – Patient. https://www.cancer.gov/types/lymphoma/patient/adult-hodgkin-treatment-pdq

- National Cancer Institute. Aggressive B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment (PDQ) – Health Professional. https://www.cancer.gov/types/lymphoma/hp/aggressive-b-cell-lymphoma-treatment-pdq

- National Cancer Institute. Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment (PDQ) – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK66057/

- National Cancer Institute. PDQ Pediatric Cancer Treatment Summaries. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/pdq/information-summaries/childhood-treatment

- National Cancer Institute. Colon Cancer Treatment (PDQ) – overview statements on metastatic disease. https://www.cancer.gov/types/colorectal/patient/colon-treatment-pdq

- American Cancer Society. Treatment of Stage IV (Metastatic) Breast Cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/treatment/treatment-of-breast-cancer-by-stage/treatment-of-stage-iv-advanced-breast-cancer.html

- National Cancer Institute. Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment (PDQ) – “curative in only a few” for limited stage. https://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/hp/small-cell-lung-treatment-pdq

- National Cancer Institute. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment (PDQ) – metastatic settings. https://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/hp/non-small-cell-lung-treatment-pdq

- National Cancer Institute. Pancreatic Cancer Treatment (PDQ). https://www.cancer.gov/types/pancreatic/patient/pancreatic-treatment-pdq

- National Cancer Institute. Prostate Cancer Treatment (PDQ) – metastatic disease. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/patient/prostate-treatment-pdq

- National Cancer Institute. Esophageal Cancer Treatment (PDQ) – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65900.1/

- van Hagen P, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer (CROSS). N Engl J Med. 2012. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1112088

- Shapiro J, et al. Long-term results of the CROSS trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanonc/article/PIIS1470-2045(15)00040-6/fulltext

- Al-Batran SE, et al. FLOT4-AIO perioperative chemotherapy in gastric and gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. Lancet. 2019. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)32557-1/fulltext

- Cancer Research UK. Treatment for Oesophageal Cancer. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/oesophageal-cancer/treatment

- National Cancer Institute. Chemotherapy and You – Infection risk and neutropenia. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/patient-education/chemo-and-you

- Sturgeon KM, et al. Updated systematic review of exercise and understudied outcomes including CIPN. Cancer Med. 2023. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10757127/

- National Cancer Institute. Cognitive Problems After Cancer Treatment. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects/memory

- National Cancer Institute. Second Cancers Caused by Cancer Treatment. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/radiation/second-cancers-caused-by-cancer-treatment

- American Cancer Society. Second Cancers After Chemo and Radiation. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/survivorship/long-term-health-concerns/second-cancers-in-adults.html

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Computed Tomography (CT) – Benefits/Risks. https://www.fda.gov/radiation-emitting-products/medical-x-ray-imaging/computed-tomography-ct

- RadiologyInfo.org. Radiation Dose from X-ray and CT Exams. https://www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info/safety-xray

- American College of Radiology. Statement on JAMA CT-scan radiation study. https://www.acr.org/News-and-Publications/Media-Center/2025/jama-ct-scan-radiation-study

- RadiologyInfo.org. How much dose do I get. https://www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info/safety-hiw_07

- RadiologyInfo.org. Body CT – patient information. https://www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info/bodyct

- NICE Guideline NG148. Acute kidney injury – prevention, detection and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng148

- NICE Visual Summary – Iodine-based contrast media risk assessment. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng148/resources/visual-summary-pdf-13551376429

- Clinical Radiology review on NG148 contrast recommendations. https://www.clinicalradiologyonline.net/article/S0009-9260%2820%2930630-9/fulltext

- Bai XL, et al. Impact of exercise on health outcomes in people with cancer. Br J Sports Med. 2025. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/59/14/1010 and PDF https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/bjsports/59/14/1010.full.pdf

- Sturgeon KM, et al. Updated systematic review of exercise on understudied outcomes in cancer survivors. 2023. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10757127/

- Cochrane. Yoga after treatment probably reduces cancer-related fatigue slightly in the short term. https://www.cochrane.org/evidence/CD015520_does-yoga-relieve-cancer-related-fatigue-people-cancer

- de la Fuente M, et al. Chemotherapy-induced dysbiosis – review of mechanisms and consequences. Frontiers in Oncology 2020 and subsequent reviews; accessible summary: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7243601/

- Saligan LN, et al. Inflammation and fatigue in cancer survivors – The Oncologist review. https://theoncologist.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/onco.14354

Subscribe to stay connected