Two Weeks on a Knife-Edge, 1st to 17th December

Some stories are neat and tidy, and then there are true ones. This is a true one.

In the grand span of fourteen days, I said goodbye to my brothers at Heathrow. I started a drug I hoped would help but stopped when pain required something stronger. I sat in two clinics where the same disease was framed with two different moral languages. I signed a chemo consent form using my pen and kept my agency with both hands. Hospice was penciled in for January, and I said “not yet.” I bought a silly 4.4-litre V8 because hope sometimes needs a steering wheel. I drove to the place we got engaged and arrived to a power cut. I ate a toastie like a civilian and paid for it like a patient. I slid into an outdoor pool so cold it simplified the meaning of courage. I received a kindness I can’t repay. I spent a weekend in the hospital listening to death breathe through the curtains while I waited for pain relief that made the world tolerable but blurry.

On the seventeenth, I laid out my clothes for infusion day like a man packing for weather he did not choose. The calendar said chemo and immuno tomorrow. My body said no more delay. My mind said not passive.

If Part 3 was about building a day I could repeat, and Part 4 about the many losses we experienced, this chapter shows what happens when you try to live that day whilst the world keeps throwing bricks at your head. The bricks are not the story. What you build with them is.

1st December, Departures, spreadsheets, and a ridiculous key

My brothers flew back to Australia on the first. Airports make grief appear organised. You queue. You scan. You pretend you’ll do this again soon. We hugged like people who knew the next time might not happen on schedule. The house felt lighter and heavier at once – quiet where laughter had been, loud where worry now sat.

So I did what I do when emotion outgrows language: I made a list. HBOT bookings (resume after travel). Pain scores. Foods that didn’t set my chest on fire. A line to myself: be kind even when your inner manager wants a quarterly review.

And because I am me, I added one more item. My oncologist said I’d likely be able to drive myself to and from chemo. I took that sentence as a prophecy and bought a second car. Not sensible. Not hybrid. Not quiet. A ridiculous 4.4-litre V8 BMW, it did at least have four seats. We called it the chemo commuting car for a day until Axel and I rebranded it Superjet Blaze because he’s three and understands the physics of morale. He also proposed naming my tumor Dave, in case Superjet Blaze needed a villain to outrun. It’s hard to argue with logic like that when you want your children to believe their father is still moving.

Sometimes hope looks like a treatment plan. Sometimes it looks like a ridiculous key in your pocket.

2nd December, A week of LDN that didn’t last

On the second, I had a consult for low-dose naltrexone, with a well known scottish pharmacy (if you know you know). LDN is ordinary naltrexone (a drug normally used to help those with opioid addictions) in tiny, daily doses. The idea is that brief receptor blocking nudges your own endorphins and may calm microglia and TLR4, reducing immune response. It lives where pain science, immunology, and oncology overlap. I started it. I wanted it to work.

A week later, my pain changed. I needed the option of opioids. LDN and opioids do not mix. You can either block the door or walk through it; you can’t do both. I stopped the LDN – not because I thought it was nonsense, but because comfort matters. When pain interrupts sleep and makes it impossible to eat, you buy comfort so you can tackle the hard things that might help. LDN went back in the drawer labeled maybe later, and I continued.

Mechanism matters. Timing matters more.

3rd December (morning), Cromwell clarity

My appointment with Dr. Andy Gaya at the Cromwell hospital (London) slipped from the second to the morning of the third. He was worth the wait. He didn’t sell me a miracle or despair. He confirmed the map we were already preparing for – serious, inoperable, involved – and then did the rare thing: he pointed. Speak to Dr. Hari Kuhan. Look at next-generation sequencing. Profile the disease you actually have, not the statistical average.

Direction is a bigger gift than comfort in these situations. I left feeling clear – not just a case to be acted upon, but a person who could act.

4-6th December, Chasing a map, a consent room, hospice on the calendar

The sequencing chase

On the fourth, I had an opening call with Astron Health, whilst also speaking with other labs before and after – some in the U.S., some here, some in functional medicine circles. Everyone had a pitch. I wasn’t shopping for certainty. I was shopping for context: how samples are handled, what the data looks like, who helps interpret it, what becomes actionable and what becomes decoration. Within a day or so, I made my choice and moved forward – before we left for Cornwall. Another brick in a wall I hoped would hold.

Until Dr. Gaya mentioned Next Generation Sequencing (NGS), I hadn’t considered it. He opened a door; I walked through and checked the floorboards.

The consent room

On the fifth, I went to see Dr. Hill. We started on what sounded like common ground. She said she was open to “alternative” approaches. When I outlined my complementary plan – actual molecules, known interactions, safety rails, sequence logic – she quickly retreated. She’d heard “alternative” and pictured yoga.

I like yoga. I don’t mistake it for a drug.

Her tone dropped a few degrees. She looked down her nose and called my approach “stupid” and “dangerous.” She said people who follow such routes often die earlier and in a lot of pain. She threatened to pull my care if I continued. Then came the fear tactics: sign the chemo consent now. I have qualifications in psychology and I’ve spent years in compliance chasing the worst of the worst scammers, fraudsters, and financial criminals. I know pressure when I feel it. I can map the tactics whilst they’re happening. The difference this time was that it wasn’t a scammer trying to get a bank login. It was a doctor trying to get me to consent to chemo. I wasn’t having it from the scammer; I sure as s**t wasn’t having it from the doctor.

A nurse stepped in and did what good people do in rooms where the air has gone thin. She said, clearly and kindly, “If you sign, you can still back out any time before infusion.” That one sentence put oxygen back in the conversation. I signed – not as surrender, but as a way to keep my options open and the ball rolling.

Then they brought in an NHS nutritionist. The advice was simple and wrong for me: gain weight to cope with chemo – high sugar foods and lots of ice cream were recommended. I kept my face polite and my plan intact. Smaller meals. Vegetarian keto. Nothing acidic. Nothing spicy. No sugar/carb loading. A plan you can’t live with isn’t a plan.

Here’s the part that matters: at this point, I initially said no to chemo. Not because I was frightened of it. Dr. Hill herself said the gains would be minimal. The numbers were brutal: maybe a month or two beyond my prognosis, paid for with months of feeling poisoned. I wanted my boys to remember a father who could get on the floor and play trains, who could pick them up and hug them – not a ghost sweating in bed because the medicine that might buy time had exhausted the life inside it. If the choice was three good months with them or twelve sick ones apart from them in the same house, I would choose the three – all day, every day!

Later that week, data changed my mind. Not pressure. Evidence. A chemo sensitivity test suggested my tumor might actually respond to CAPOX, a different drug than had been originally suggested, but one that was on the table nonetheless. That result – within the same fortnight – framed chemo’s place in my plan. Not as the whole answer. As a piece that might work, provided I stitched it into a broader, logical approach I could stand behind.

Hospice, penciled in

Around the sixth, the Sue Ryder nurses came to the house – kind, efficient, human. They told us the NHS had flagged me for a hospice bed and wanted to get me booked in for January. Later, the date became March. We said no, thank you – not because we didn’t respect the service, but because we were not done fighting and hoping. We told them we’d reach out when we were ready. My map did not yet include a bed with no return ticket.

People hear that and think denial. But it wasn’t denial. It was rebellious refusal – the same kind that keeps you breathing in cold water when your body is trying to climb out.

9-10th December, Pre-chemo, family arrivals, and the road to The Scarlet

Monday the ninth was for the pre-chemo assessment at Royal Berkshire. There were blood tests, vital sign checks, and logistics – a careful routine that manages hundreds of people each week whilst trying to be kind to them all. My dad flew in that day. Liz, his then-ex, arrived the morning of the tenth to help him support us. This is how families respond when the world feels off-kilter. Resumes don’t matter. Actions do.

On Tuesday the tenth, Ana and I did something bold: we drove to The Scarlet hotel in Cornwall, the hotel where we got engaged. Call it sentimental if you want, but I see it as strategic. We didn’t have a honeymoon period. We stole three days and called it oxygen.

When we arrived, there was a major power cut. No hot water, only rechargeable lamps, and a spa running on effort and apologies. I’ve learned to respect the universe’s sense of humor. It may not be kind, but it is consistent. We laughed because crying felt like a luxury we couldn’t afford.

The following morning Ana tried the spa, but sadly they wouldn’t give her a massage due to her recent lobectomy. Stitches took priority over spa treatments. I, trying to appear like an ordinary person on holiday for Ana’s sake, gave in to a toastie one evening. That decision resulted in barbed-wire pain that wrapped around my ribs and wouldn’t relent for days. The oesophagus doesn’t care about the calendar.

We also tried to have an afternoon out, visiting Truro’s (where I once lived) Christmas market – a stroll through a part of my past (college years, ordinary worries, lots of fun memories and forgotten nights). I felt too unwell to enjoy it, so we turned back after less than an hour. It was a failure on social media but a wise choice in real life.

There were some victories. I sat in a hot tub on the clifftop, sweated in the sauna, and braved the outdoor natural pool – which was colder than any ice bath I’ve tried. I counted to sixty, then another sixty, and reminded my nervous system that the world is bigger than a hospital ward. I can choose to be shocked, not just to suffer.

I paused HBOT for the trip and the hospital days to follow, but I packed my PEMF mat. Rituals matter when routines fall apart. You learn to carry small bits of normalcy like protective charms.

Thursday the twelfth, Ana’s birthday, felt like a candle fighting the wind. We celebrated under rechargeable lamps, shared private jokes, and made something special out of simplicity. I stuck to th very small amount of foods that wouldn’t upset my chest and pretended that was a normal way to celebrate life. We’ve had better birthdays. We’ve had worse days. Perspective isn’t comforting; it’s just reality.

Then kindness did what medicine couldn’t. Our dear friend Mark, Axel’s godfather, rang up and paid for our stay without telling us. We found out later, when we went to settle the bill on our departure. I don’t have an explanation for why some gestures feel like support and keep you upright. I just feel so incredibly grateful to have such amazing people in my life. That will have to suffice.

We drove home on Friday the thirteenth. The date felt threatening at first, but then it shrugged it off. Dad and Liz flew back to Guernsey a few hours after we returned. The boys had an amazing week doing puzzles with Grandpa Sam and Liz. We were exhausted but grateful. Sometimes that’s the best we can get.

14-16th December, The corridor between worlds

That weekend reminded me that story arcs matter to readers, not to bodies. Pain flared up on Saturday, and I was admitted back into hospital. At first, there was no available bed. I spent two days/nights on a gurney in A&E, stuck in fluorescent limbo. The staff were saints managing paperwork in chaos. I lay there listening to the unique sounds of hospital nights – monitors beeping, curtains stirring, footsteps rushing toward alarms, and the metallic sound of a trolley floor.

By Monday, I was moved – not to a quiet room but to a ward filled with dementia and endings. On the first night, an elderly woman in the bed next to me died with a loud struggle. No curtain can mask that noise. For the following days, a gentleman with advanced dementia cried out through the night, lost in a space that medicine recognises but cannot fix. The staff did everything humanly possible within a system that often lags and lacks beds. I wanted out so badly it made my teeth ache.

They tried pregabalin and oxycodone (Morphine made me nauseous). The combination dulled the sharp edges but blurred them as well. Trade-offs were everywhere. The pain was just as I had feared: a pressure radiating from the tumor’s impact on a cluster of nerves near the solar plexus, made worse by eating. After most meals, I ended up lying on the floor for 60–90 minutes, negotiating a truce with my own body. That weekend, it stopped negotiating.

I’m not writing this to be dramatic. I’m writing it to reflect that truth without detail becomes theory. This is the detail. It’s also why I keep trying to build a day I can live with. The alternative is to learn the sounds of other people’s departures, and I’m not ready for that soundtrack.

On Tuesday the seventeenth, I came home. The pain plan went with me, as did my refusal to accept it fully. I was told I might need pregabalin and oxycodone for the long term; I accepted that possibility but started planning my way out. One step at a time.

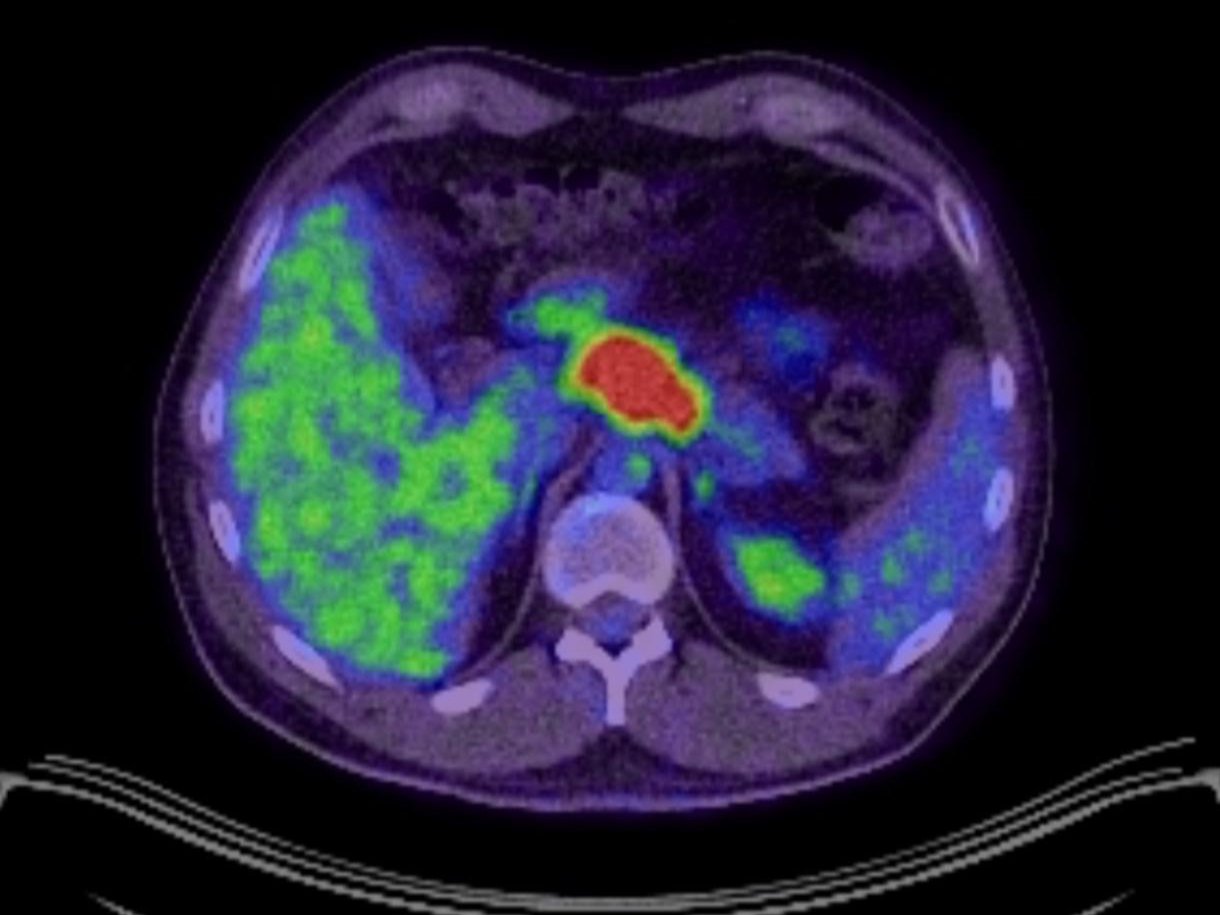

During this same period, the chemo sensitivity test I arranged returned with usable results. It didn’t guarantee anything. It just offered a possibility. It shifted the decision from “not for me” to “maybe for me – if I control the inputs and protect the boundaries.” Simultaneously, the PD-L1 test came back at around 9.9 – a fraction below the usual lower limit – but Dr. Hill still fought to get me pembrolizumab. The paradox is important: this is the same doctor who had threatened to cut my care but also worked to secure my place on immunotherapy. People are complex; so is the NHS.

17th December, The night before the drip

I wanted the day before chemo and immunotherapy to look like my own. I wanted to wake up, stretch, breathe, take a gentle walk, eat according to the plan – vegetarian keto, small portions, nothing acidic or spicy. I wanted to read and go to bed early. I wanted to lay out my clothes like a child preparing for a school trip, because control feels comforting when the next day involves needles.

Instead, I woke up in a hospital bed. Tired. Sore. Hungry – I wasn’t able to eat, as all they had available were plain cheese sandwiches. Not the easiest thing to pallet for an oesophageal cancer patient. Thankfully they released me and I was home that afternoon.

The nurse’s words from the consent room were tucked into my chest pocket: You can still change your mind before infusion. I could. Overall – with a chemo sensitivity test suggesting a shot, a PD-L1 decimal point that someone argued through, and a plan that I found scientifically sound – I decided to proceed.

My rationale was straightforward yet complex. Standard care made sense where it applied. Pembrolizumab alongside CAPOX because the biology suggested it could work. Clever additions sequenced thoughtfully. I wanted to respect the NHS without surrendering control over my choices. Sequence the order, not just the elements. I wasn’t against chemo; I was against passivity.

I reflected on the past two weeks. It broke down like this:

- Brothers in Australia and a house that echoed in emptiness.

- LDN started, then stopped, because pain required stronger painkillers, and sometimes the right tool is the unglamorous one.

- Dr. Gaya confirmed my condition and pointed me toward Dr. Kuhan and NGS.

- Astron call on the fourth; others before and after; my goal not to seek certainty but to find context – decided and pushed ahead within days.

- In a consent room where “alternative” went from yoga to “stupid” and “dangerous,” where a doctor tried to intimidate me, and a nurse reminded me that consent is not a trap. I signed and kept my plan.

- An NHS nutritionist recommending sugar and ice cream to “gain weight,” whilst I chose smaller vegetarian-keto meals because my metabolism wasn’t an idea – it was a tool.

- Sue Ryder offered to book hospice care for January or later in March, and we said not yet.

- Pre-chemo at Royal Berks, with Dad and Liz arriving. We had three stolen days in Cornwall because breathing matters when you feel submerged.

- A power cut, a toastie mistake, a victory in a cold pool, and a friend’s kindness that made me feel supported in a way medicine cannot.

- A&E gurney limbo, a ward that echoed with endings, and pregabalin plus oxycodone forming a truce I intended to dissolve later.

- A chemo sensitivity test suggesting I give it a try, and a PD-L1 decimal point that didn’t stop pembrolizumab.

- Superjet Blaze on the drive – ridiculous, loud, impractical – but the exact signal I needed to tell myself: we are still moving forward.

It didn’t seem like progress. It was positioning. Every conversation, every boundary, every polite no, every chosen shock, every small meal, every walk, and every line I drew moved me a centimeter away from surrender and a centimeter toward autonomy. I wasn’t better yet. I wasn’t done either. I was prepared.

Tomorrow would bring machines, drips, beeping monitors, and the therapist’s worth of small talk that happens in rows of vinyl chairs. Tonight, I lay in my own bed and allowed acceptance and refusal to coexist. They don’t get along. They agree on one thing – both want their goal.

I wasn’t giving up. I was gearing up.

Postscript, The car and the child

I keep thinking about that ridiculous V8 key. It wasn’t practical, but it was a statement. It sat in my pocket like a promise for later. Axel thinks the car’s name sounds faster than cancer. I think he’s right. He also named the tumor Dave. It’s tough to treat a villain seriously once your child has given it a silly name like a goldfish. There’s a lesson in making monsters less intimidating. If you can create a name that makes your family laugh, you’ve already taken a piece of power away.

On the morning of the eighteenth, I would put the key in my pocket. I would drive to the hospital. I would sit in the chair. I would let medicine do its job, alongside my plan. And if I could, I would drive myself home again.

That’s the promise I made the night before the drip. Not a promise to win. A promise to arrive.

Subscribe to stay connected