Introduction. The Christmas Plant I Inject

It’s a strange sentence to write: I self-inject mistletoe. The same stuff people hang above doorways in December is one of the most studied integrative therapies in cancer care. It’s widely used in Germany and Switzerland but mostly ignored by the NHS, and it’s now part of my treatment plan.

I consult with the National Centre for Integrative Medicine (NCIM) in Bristol. They send it through a partner pharmacy, it arrives at my home, and I give myself the injection three times a week. It’s simple, routine, and not glamorous at all. I haven’t felt any dramatic changes since starting – no sudden bursts of energy or overnight tumour shrinkage – but the science and clinical track record in Europe were convincing enough to keep it in my regimen.

This post is about what mistletoe therapy is, how it’s thought to work, what the evidence shows (and doesn’t), how I use it, and why I believe UK cancer care should take it more seriously.

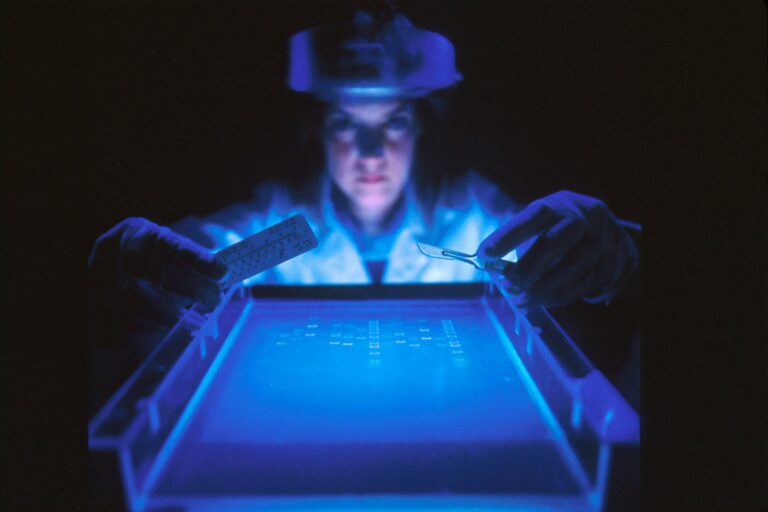

What Is Mistletoe Therapy?

“Mistletoe therapy” refers to sterile extracts from the European mistletoe Viscum album, produced under strict standards and given primarily as subcutaneous injections several times per week. You’ll find brand names like Helixor®, Iscador®, and Abnoba, often followed by a letter indicating the host tree (for example, Quercus for oak, Pinus for pine).

Doses are usually increased until there’s a mild local skin reaction or a temporary low-grade fever – this indicates the immune system is responding.

Historically, this therapy has roots in early 20th-century European integrative medicine. Today, physicians in several European countries prescribe it as a supplement to standard care, focusing on quality of life, symptom control, and, in some studies, potential survival benefits. In the UK, access is mainly through private integrative clinics like NCIM.

How It’s Thought to Work (The Mechanisms, Plainly)

Mistletoe extracts are not just one molecule; they are complex mixtures. Three components receive the most attention:

- Mistletoe lectins (ML-I/II/III): Protein-sugar complexes that can trigger programmed cell death and stimulate immune activity.

- Viscotoxins: Small peptides that have direct toxic effects in a lab setting.

- Triterpene acids: Fat-soluble compounds (like oleanolic and betulinic acids) that show anti-inflammatory and pro-apoptotic signals in early studies.

Simply put, mistletoe seems to support immune function (boosting NK cells, macrophages, T-cell activity), promote programmed cell death in tumour cells, and reduce inflammation, which may help patients tolerate treatment better. None of this is magic; it’s mostly biochemistry that we already understand from other immune system modifiers, just delivered through a plant-based extract.

What the Evidence Actually Shows

Let’s be clear. If you’ve heard “mistletoe cures cancer,” that’s marketing (or influencer clickbait) – not medicine. The peer-reviewed evidence looks like this:

1) Quality of Life (QoL): the strongest signal

- Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses (including newer ones) report meaningful improvements in quality of life for patients receiving mistletoe alongside standard care – across areas such as fatigue, pain, sleep, and overall well-being.

- A 2020 meta-analysis published in BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies found mistletoe is linked to a medium-sized improvement in cancer-related quality of life.

- A more recent analysis focusing on cancer-related fatigue also suggested benefits.

These studies are not flawless – there are issues with variability and bias – but the quality of life signal appears consistently.

2) Survival: promising in some cases, not definitive

- Several European studies (including some observational and randomised trials) have suggested survival benefits in certain cancers (like breast, lung, and gastrointestinal), but the results vary and are often hampered by methodological issues (like non-blind designs and selection bias).

- A pooled analysis of patients treated with Iscador reported improved survival, whilst also noting possible publication bias.

- The US National Cancer Institute’s PDQ review states plainly: survival improvements have been reported, but study weaknesses prevent firm conclusions.

This is an area where modern, UK-led practical trials would be beneficial.

3) Safety and tolerability: generally favourable

Over decades of use, mistletoe is generally well tolerated.

- The most common side effects are local reactions at the injection site (redness, warmth, swelling), temporary fever or flu-like symptoms, and, rarely, allergic reactions.

- Many programs intentionally adjust doses to provoke a mild reaction as an immunological cue.

- Serious side effects are uncommon when products are prescribed and supervised properly.

(Note: intravenous mistletoe is being researched; early studies suggest it’s feasible and safe, but IV use remains experimental and should be limited to clinical trials or specialised centres.)

Bottom line: The strongest benefit is improved quality of life and treatment tolerance. Survival signals are intriguing but not conclusive. Safety is generally good with medical supervision.

Why I Use It (Even Though I Don’t “Feel” It)

My next-generation sequencing (NGS) highlighted mistletoe as relevant to my case – not as a magic solution, but as a supplementary treatment that could support my immune system and overall health.

With guidance from NCIM, I now receive it at home and self-inject. I haven’t noticed a clear daily effect, and that’s fine with me. Not every treatment needs to be dramatically impactful to be worthwhile. If a therapy improves my chances of coming out the other side of this, sleeping better, or simply feeling more like myself – that’s significant. I should also add that it may also have helped me to get through chemo, back in those dark months.

Most importantly, mistletoe fits into my broader, holistic approach: ketogenic diet, off-label metabolic therapies, IR sauna, HBOT, high-dose vitamin C, red-light therapy, pEMF, breathwork, and an ongoing focus on air, water, and my kitchen environment – amongst other things.

As I hope you’ll know by now – I’m not looking for a single miracle cure – and anyone (outside of a medical breakthrough) who says they have one is selling snake oil. Instead, I’m building a comprehensive strategy. Mistletoe earned its place because the cost-benefit analysis seems reasonable, and the European experience is compelling.

The UK Gap – and Why It Frustrates Patients

In parts of Europe, mistletoe is a common part of integrative cancer treatment. In the UK, it’s largely overlooked. Patients searching NHS resources won’t find structured access or guidance, despite decades of safe use in other countries and a substantial (though imperfect) evidence base – no pharma company wants to pay for trials on things that they can’t patent and earn off of.

This gap forces people into a false choice: ignore it because it’s labelled “alternative” or pursue it independently without clinical support. We can do better!

The NCIM is one of the few exceptions in the UK, offering integrative consultations and prescriptions through regulated channels. Their patient information is clear and cautious: mistletoe is not a curative cancer treatment but a supportive therapy used alongside traditional care to enhance quality of life and resilience. That honest and supportive framing is precisely what’s lacking on a larger scale.

The NCI’s PDQ (in the US) serves as a useful model. It neither “endorses” nor “dismisses” but summarises the evidence, highlights limitations, and keeps the information current.

Imagine if UK guidance did the same – acknowledging potential benefits, safety guidelines, and how to access reputable products under medical supervision. That alone would protect patients from poor-quality products and misleading claims.

Practicalities: Forms, Dosing, and Expectations

Products & host trees: Iscador, Helixor, Abnoba, and others create preparations from mistletoe gathered from various trees (like oak, apple, or pine). Clinicians sometimes select a preparation based on tumour type, the host tree, and the patient’s response, though direct comparisons between them are limited.

Route & schedule: Most programmes use subcutaneous injections a few times a week, with gradual dose increases until there’s a mild local reaction or a short fever. Some clinics are also looking into intravenous protocols as part of trials; outside of trials, IV use should be considered experimental.

Duration: Treatments often last for months to years and may be paused or adjusted around surgery, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy depending on the treatment plan.

What to expect: Many patients notice local redness or warmth at the injection site; some feel flu-like symptoms for a day or two when starting. Dramatic changes are not common – my experience has been steady and uneventful.

Safety, Interactions, and Who Should Avoid It

- Common effects: local redness, swelling, itching; temporary fever and malaise.

- Allergy: while rare, it is possible; clinics typically closely monitor first doses.

- Hematologic malignancies: some programs proceed with caution in cases of certain leukaemia or lymphoma; you should discuss this with a specialist.

- Autoimmunity & immunotherapy: mistletoe alters immune function; clinicians will consider timing and interactions with checkpoint inhibitors based on individual cases.

- Pregnancy: caution is advised, or it should be avoided unless specifically recommended by a specialist.

- DIY warning: use only regulated products under medical supervision; quality and composition can vary, and intravenous use should be confined to trials or specialised centres.

What the NHS (and UK Research) Could Do Next

This isn’t about blindly adopting European practices. It’s about following good science and prioritising patient-centred care. Three straightforward steps could make a significant difference:

- Conduct practical UK randomised controlled trials focused on quality of life and treatment tolerance endpoints (fatigue, pain, dose intensity, unplanned hospital admissions), with survival tracked but not as the sole focus. The fatigue and quality of life meta-analyses support this emphasis.

- Create guidance pages (NHS, CRUK) that outline the current evidence (benefits, limitations, safety), provide lists of reputable access routes, and discourage unsupervised use. The PDQ model serves as a solid template.

- Collect data from UK clinics to track real-world outcomes, adverse events, and healthcare use (like fewer emergency room visits during chemotherapy) – signals that health systems value.

Until then, patients seeking mistletoe will continue to seek it out privately – and many will do so wisely. But, it would be better if they didn’t have to navigate it alone.

Where the Evidence Is Moving (and Why It Matters)

Two trends are worth paying attention to:

- Better-designed trials: We are starting to see more rigorously designed studies and standardised outcome measures. They are not perfect, but they are showing improvement.

- Route of administration: A 2023 Phase I study of intravenous mistletoe in advanced cancer showed it is feasible and acceptably safe, with indications of reduced symptom burden – but IV use is still under investigation. The subcutaneous method remains the standard for routine integrative practice.

None of this transforms mistletoe into a miracle cure. But it highlights the importance of a careful, evidence-based approach – especially in areas (quality of life, fatigue, treatment tolerance) that are crucial to patients and caregivers.

How It Fits My Protocol (and Why I Kept It)

My treatment approach is designed to be multi-modal: diet (vegetarian keto), metabolic support, breathwork, environmental detox, and carefully selected off-label drugs. Mistletoe is part of the immune support corner of that strategy. It’s low risk, supervised, and likely helpful for fatigue and treatment tolerance – areas that impact daily life far more than any abstract biomarker.

I also adopt a systems perspective rather than thinking in isolated segments. If a therapy enhances mitochondrial function, blood flow, immune response, or simply sleep – those benefits can accumulate with the rest of my regimen. Dealing with cancer is a long battle; small advantages add up.

The Fine Print (Because Safety Matters)

- This post is not medical advice.

- Mistletoe products are pharmacy-grade injectables in Europe; use them only under the supervision of a clinician.

- Intravenous mistletoe is experimental; avoid it outside of trials or specialised programs.

- If you are undergoing immunotherapy or have blood cancers, discuss timing and risks with your medical team.

- Report all herbs, supplements, and injectables to your oncology team – transparency helps prevent harm.

Conclusion. Quiet Therapy, Real Potential

If you’re expecting a glowing endorsement, I don’t have one. Mistletoe hasn’t cured my cancer or turned me into a superhero. What it does is help me maintain my well-being: it eases fatigue, makes treatment a bit more manageable, and strengthens my overall health. In a world that often defines success only by tumour measurements, these gains are significant.

I also believe it reveals a broader truth about UK cancer care: whilst we excel at medications and surgical procedures, we often undervalue quality-of-life improvements with favourable safety profiles and years of European experience. We can address this with research, clear guidelines, and a willingness to learn from other countries.

Sometimes, the best allies in this fight aren’t the loud ones. They’re the quiet, consistent treatments that you hardly notice each day – until you stop and realise you feel a bit more like yourself. For me, mistletoe is one of those treatments.

References

- NCI PDQ (Health Professional): https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/cam/hp/mistletoe-pdq

- MSKCC “Mistletoe (European)” overview: https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/integrative-medicine/herbs/mistletoe-european

- NCIM (UK) – Mistletoe Therapy page: https://ncim.org.uk/treatments/mistletoe-therapy

- NCIM – Mistletoe Patient Information (PDF): https://ncim.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/NCIM-Mistletoe-Therapy-Patient-Information-Feb25.pdf

- Quality of life meta-analysis (BMC Complement Med Ther, 2020): https://bmccomplementmedtherapies.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12906-020-03013-3

- Cancer-related fatigue meta-analysis (Support Care Cancer, 2022) – full text: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9213316/

- Survival pooled analysis (BMC Cancer, 2009): https://bmccancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2407-9-451

- Mechanisms review (open-access overview): https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4058517/

- Mechanisms review (lectins focus, 2021): https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S266703132100021X

- Phase I trial of intravenous mistletoe (2023) – full text: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9973409/

Subscribe to stay connected

Great post Dan on Mistletoe, really do hope the NHS catch up on this but without big Pharmaceutical backing and incentives to make money, I guess private is the only safe path for now. Great to see another natural source delivering benefits to people affected by cancer.

I’m not sure who this Dan fellow is Paul, but he sounds like a truly wonderful person 😜

You’re absolutely right though — without the financial incentive, the NHS will always be slow to move on things like mistletoe. It’s a shame really, because the data and patient outcomes are already compelling enough to warrant serious attention. Hopefully change comes sooner rather than later.

Thanks for taking the time to read and comment — really appreciate it.